In a Swimmer’s Two-Year Quest, a Final 21-Mile Challenge

August 6, 2017

On Thursday, Antonio Argüelles, 58, of Mexico set out to cross the North Channel in his attempt to complete the Oceans Seven.

Antonio Argüelles, 58, rose near dawn Thursday hoping for good fortune.

He had arrived in Donaghadee, Northern Ireland, from Mexico City a few weeks before to prepare to swim 21 miles of the frigid, tempestuous North Channel between Northern Ireland and Scotland.

He’d already knocked off six of the seven arduous channel crossings that make up the so-called Oceans Seven, open water swimming’s answer to climbing the Seven Summits of mountaineering. And if the weather cooperated, he would have a chance to complete this crossing and become the first Latin American, the seventh person ever and the oldest to complete the Oceans Seven.

Nature seemed to have other plans. Argüelles recalled that morning later in an interview by telephone. As he sipped his coffee and stared to the horizon, all he could see were dark, foreboding skies spreading a summer rain over a gray-green sea.

To complete an official crossing of the North Channel, a swimmer must hire a boat and an official observer, or referee, through the Irish Long Distance Swimming Association.

As open water swimming’s popularity has increased, bookings have become a difficult wrangle. Argüelles reserved his spot nearly three years in advance, and was granted a one-week window from July 28 to Aug. 4 for weather good enough to try. It’s virtually impossible to make the crossing in winds above 10 knots, and after Argüelles had spent tens of thousands of dollars and dedicated two years toward this singular pursuit, all he could do was wait, and hope the weather improved.

On Thursday morning, he caught a break, and at 7:15 a.m., with support crew in tow on a boat, he jumped into the ocean, wearing only the marathon swimmer’s minimalist uniform: swimsuit, cap and goggles. In short order, he started swimming to Scotland.

The water was not especially rough, and no colder than expected, about 55 degrees, yet Argüelles, his skin coated with zinc oxide and petroleum jelly, was sluggish.

In the third hour, with the sun now shining, he found his rhythm, stopping every 30 minutes for water, a shot of protein gel and perhaps some steamed potatoes.

During feeds, he treaded water while an observer from the swimming association ensured that his support team didn’t make physical contact with Argüelles, a violation that would void his attempt.

In the North Channel, timing is everything, and it’s not uncommon to come within a mile of shore only to be denied glory by tides and wind and cold, no matter how hard you swim or how much you burn for it.

The swims in the Oceans Seven, chosen for their familiarity and geographic distribution, present all sorts of hazards and weather patterns.

The chilly and choppy 21-mile-long English Channel and the 20-mile Catalina crossing between Santa Catalina Island and mainland Southern California may be the most famous of the bunch. High winds, rugged surf, bull sharks and Portuguese man-of-war make crossing the 27-mile Kaiwi Channel between Oahu and Molokai particularly difficult. The 16-mile Cook Strait between New Zealand’s North and South Islands is famous for sharks, too, which also school around tuna boats in Japan’s roughly 12-mile-long Tsugaru Strait, while the 10-mile Strait of Gibraltar, between Spain and Morocco, is one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Still, though it lacks sharks, the North Channel is by far the most feared.

“All things considered, North Channel is the most difficult because of the cold water, jellyfish and tidal flows,” said Steven Munatones, founder of the World Open Water Swimming Association. “The currents and winds fluctuate.”

But it wasn’t the currents or the North Channel’s notorious jellyfish blooms that frightened Argüelles going into the swim. It was hypothermia. “I’m from Mexico,” he said the day before his attempt. “We don’t have cold water.”

The oldest of four brothers, Argüelles grew up in the Coyoacán borough of Mexico City.

In 1968, when he was 9, the Olympics came to town, and Felipe Muñoz Kapamas became the first Mexican to win a gold medal, in the 200-meter breaststroke. His feat captivated Argüelles, and he took up swimming. Five years later, after his father lost his job, Argüelles started selling Speedo caps and goggles at swim meets to help feed the family.

A Speedo executive, Bill Lee, took notice and became his mentor and benefactor.

Argüelles moved in with Lee’s family in Northern California and swam for one year at Stanford, narrowly missing out on making the Mexican Olympic team in 1976 and 1980.

In the 1990s, having stopped swimming, he started a business to bring competitive triathlons to Mexico and completed his first of five Ironman distance races (2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike and 26.2-mile run) in Kona, Hawaii, in 1994.

In 1999, he went back to swimming, and for his 40th birthday he swam the English Channel for the first time.

He has also swum around Manhattan Island twice. All while serving in multiple Mexican government ministries and running a private school system he founded.

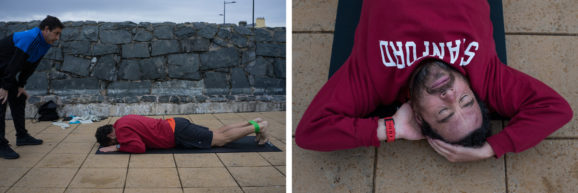

Ever since he made the commitment to complete the Oceans Seven two years ago, he has spent weekends training. He hired a strength coach and a mental fitness coach, studied muscle activation technique, and bulked up in the gym and at the kitchen table, adding both muscle and fat until he reached 210 pounds.

He does not swim in a wetsuit.

“People ask me if I swim with neoprene,” he said Wednesday, “and I say I have my own bioprene.”

Good thing. Steep yourself in 55-degree water for, say, 12 hours without a wetsuit, and it won’t take long before your blood is shunted from your head and extremities to the core, to protect your internal organs. “That’s why open water swimmers have hallucinations,” Munatones said. “They start to lose their mental clarity because the capillaries of their brain start to close up.”

Kim Chambers, the third woman and the sixth athlete to complete the Oceans Seven, said, “You are a bit delirious, as if emerging from general anesthesia.”

But it wasn’t the cold that affected Argüelles when he hit a wall of exhaustion at 5 p.m. Thursday, more than 10 hours into his swim.

It was the tides.

Argüelles got caught in an eddy and was held in place for an hour. The captain of the boat noticed and informed Argüelles that he would have to swim as hard as possible to try to break through.

Argüelles, punctuating the recollection with a Mexican vulgarism, said, “I had to use all my mental training at that moment.”

He hammered away. Three hours later, he made the final 100 meters, washing in with a foaming tide just before 9 p.m. local time. Exhausted, he sat on a slick boulder and raised his arms. After a swim of 13 hours 32 minutes 32 seconds, and a total of 25.7 miles as he meandered out there, Argüelles had done it.

“Three times in my life,” he said by phone on the boat ride back to Donaghadee, “I have been this well prepared for an event: the Olympic trials in 1976 and 1980 and today. I never made the Olympics, but today I redeemed myself.”

According to Munatones, there are even bigger ramifications to consider. This is the golden age of open water swimming, with over 12,000 races held in 168 countries around the world each year, and Argüelles’s feat may inspire more people to take on the challenge of completing the Oceans Seven.

“He’s a pioneer,” Munatones said. “He set the standard in channel swimming for the Spanish-speaking world and for people over 50. To do one of the world’s most arduous endurance challenges at his age is mind-boggling.”