Racing Across Antarctica, One Freezing Day at a Time

Louis Rudd and Colin O’Brady are in the middle of a unique race across the coldest continent, and their daily tasks range from the mundane to the death defying.

By Adam Skolnick

Nov. 29, 2018

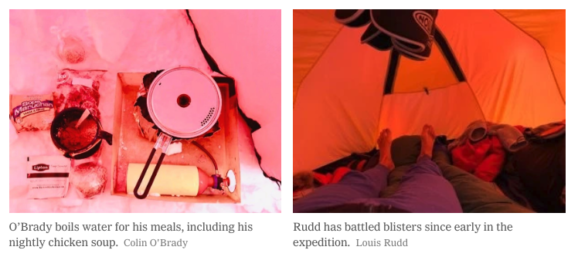

Monday was not an ideal morning to ski in Antarctica. The wind was fast, and a snowstorm was producing whiteout conditions, making the skiing feel like “being inside a Ping-Pong ball,” in the words of the American adventure athlete Colin O’Brady.

But there was no time to waste in a race to become the first person to cross Antarctica alone from shore to shore without any aid or support. So when O’Brady and Louis Rudd, a captain in the British Army, unzipped their tents and saw the misery they would experience on the 23rd day of their journey, they confronted it as if it were any other day. They would consume warm fluids and high-calorie snacks, and push through the unmatched exhaustion that comes from hauling a 300-pound Norwegian sled, known as a pulk, for 10 to 12 hours.

Each day these two competitors, who have been traveling miles apart from each other and have not communicated with each other, have emerged amid an icy desert to battle the elements and one another. They’ve felt pain and frustration, taken risks and shed tears.

As they skied through the whiteout on Monday, they stared at compasses strapped to their chests to stay on course toward the South Pole, unable to see up or down or side to side, with their sleds catching on wavelike ridges of ice known as sastrugi, forcing the occasional tumble. On this expedition, for both men, tripping and falling hard — countless times — is all part of the schedule.

6:10-7:25 A.M.

Wake-Up Calls

O’Brady wakes up at 6:10 a.m. and lights his backpacking stove on the ice in the vestibule of his tent. He boils water for his morning meal of oatmeal with extra oil and protein powder.

While he finishes breakfast, he empties his tent and packs his pulk. By then, it’s about 7 a.m., which is when Rudd wakes up and lights his stove, which he also rests in the vestibule of his tent.

Rudd’s day starts with instant hot chocolate — he’s carrying more than 15 pounds of hot chocolate powder in his sled. He also eats a freeze-dried meal of porridge or onions and eggs.

It’s all about calorie loading on an expedition like this. Though both men consume as many calories as possible, they still expend more calories than they take in. After all, there are only so many calories someone can carry in a sled and still be able to move it.

7:30-8:30 A.M.

On the Move

After breaking down his camp and packing his pulk, O’Brady clips into his harness and begins to ski at 7:30. The motion is much more like walking than it is skiing; pulling a massive sled is not exactly conducive to long, smooth skiing motions.

Rudd fills two one-liter flasks with warm water, breaks camp and packs up his gear. After a last check of his campsite, he clips into his harness at 8:30 and begins to move.

8:30 A.M.-1:30 P.M.

The Real Work Starts

O’Brady and Rudd take a similar approach to the day’s work, but with slightly different rhythms. O’Brady breaks the day up into eight 90-minute intervals. Rudd skis in eight or nine segments of 70 minutes each.

For both men, the early days of the expedition were brutal.

“The beginning was crazy,” Rudd, 49, said via satellite phone from his camp Monday night. “The weight was so heavy. I’ve never pulled anywhere near that before, and I’m not getting any younger.”

O’Brady, who spoke via his satellite phone on Thanksgiving Day, described the first four or five days as very emotional. “Crying, frustrated, physically rocked,” he said.

Both men also struggled to manage their perspiration. Sweat can be deadly in a polar environment because moisture can freeze on the skin when motion stops, which can send core temperatures plummeting toward hypothermia. Both men independently addressed the problem by skiing in just their base layers to stay cool and sweat-free. Their exertion kept them plenty warm despite the subfreezing temperatures.

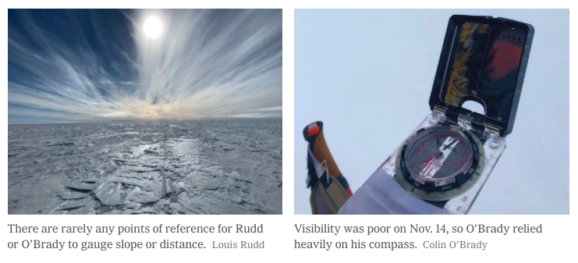

They have been climbing more than 9,000 feet from sea level to the South Pole (altitude 9,301 feet). They have felt the incline but haven’t always seen it, even on clear days, because there are rarely any points of reference they can use to gauge slope or distance.

“You know by the pulk,” Rudd said. “You’re suddenly working 10 times harder. You look around and you can’t tell you’re going uphill, but you must be because you can really feel it.”

After each segment, the men stop for five-minute breaks, taking a sip of warm water and eating a snack. O’Brady opts for a bite-size chunk of an organic, calorie-rich energy bar that his sponsor made for this expedition. Consisting of coconut oil, nuts and seeds and other ingredients, each chunk contains as many as 500 calories.

Rudd grabs a fistful of chocolate and nuts or some salami and cheese from his “grazing bag.” The salami melts in his mouth, but the cheese has been frozen solid, so he keeps it tucked into his cheek like a hamster until it thaws, as he continues to move.

1:30 P.M.

Ramen for Lunch

Rudd doesn’t bother to stop for lunch. O’Brady settles for a bowl of ramen noodles after his fourth 90-minute shift. He sits on his pulk, pours hot water from his thermos over a bowl of dried noodles and slurps away.

1:45 -7 P.M.

Finding a Rhythm

Both Rudd and O’Brady can fire up their headphones when they want to.

Rudd passes time by listening to ’80s music and audiobooks. He has already listened to a biography of Winston Churchill. O’Brady has downloaded podcasts, including The Rich Roll Podcast and The School of Greatness. He once listened to the Paul Simon album “Graceland” on repeat for an entire day. He said he enjoys the sounds of the nearly barren continent more than anything — his skis on the snow and ice, the wind streaming across the icescape.

Rudd came into this race with far more experience. He had already traveled more than 2,000 miles on Antarctica. But it didn’t take long for O’Brady to find his stride.

The biggest challenge of the first week was the sheer weight of the pulk. Week No. 2 brought an obstacle course of sastrugi. O’Brady continued to log a relatively high number of miles each day, though. Then, last week, the winds died down, and a frontal depression moved in from the Weddell Sea, bringing fog and snow. The men waded through a foot of fresh powder for four days.

O’Brady charged as many as 20 miles in one day at first, then struggled to put up a string of 12-mile days.

“I can’t control the surface conditions of the ground,” an exhausted O’Brady said on Thanksgiving, “but I know I can get out there and pull 12 hours every single day. That’s the mentality.”

Rudd had so much trouble moving through snow on Thanksgiving, he took a risk, ferrying half his gear forward two miles with snow still falling. When he returned to find the other half, it was nowhere in sight. Fortunately, he had marked the location with his GPS and was able to dig it out from under the snow, but the experience shook him. If his GPS had failed at that moment, his expedition — and perhaps his life — would have been in grave danger. Once he managed to move all of his gear to the same spot, he opted to stop for the day.

7 P.M.

11 More Steps

Most days, Rudd skis for more than 10 hours. Whenever he feels like stopping, he marches an extra 11 steps before he sets up camp.

It was once calculated, Rudd explained, that if the famed English explorer Robert Falcon Scott and his team had taken 11 more steps each day on their expedition in the early 1900s, they would have survived.

After completing the 11th step, it takes him about 20 minutes to set up camp.

8 P.M.

Settling Down

There is no nightfall in Antarctica at this time of year, but there is an end to the day of skiing.

After about 10 hours, Rudd digs out a hole for his stove and begins melting snow into water for his warm recovery drink and a freeze-dried dinner — spaghetti Bolognese or chicken tikka.

O’Brady stays on the move until roughly 8 p.m., and then sets up camp.

In good conditions, it takes him about 20 minutes to unload his pulk and pitch his tent, but in strong winds it can take much longer. One day last week, with winds gusting at 40 m.p.h. late in the day, it took him 90 harrowing minutes.

Once inside, O’Brady prepares his recovery drink and a bowl of chicken soup, then fills his two-liter thermos with water for the next day. Next, he enjoys a freeze-dried meal of his own.

Then comes more work.

There are nightly calls with their minders at Antarctica Logistics &Expeditions, the private company that arranges travel to the continent, and their expedition managers. Rudd’s team is led by Wendy Searle, a fellow polar adventurer from England. He files a daily audio blog and a picture of the day with Searle, which his sponsor posts online.

O’Brady leans on his wife, Jenna Besaw. He sends her an Instagram post and answers at least one student’s question each weeknight via his satellite router; O’Brady’s expedition is being followed by students and teachers at 104 schools around the world.

The last thing each does before bed at 11 p.m. is lay out or hang up their clothes to dry. Neither man has a change of clothes, or even fresh underwear. O’Brady did bring a spare pair of socks.

As of Friday, they were both well over halfway to the South Pole, more than one-third through their entire 920-mile traverse, with O’Brady 12 miles ahead of Rudd. In a race as long and hard as this one, however, no lead is safe.

Lately, Rudd, who has battled blisters since early in the expedition, has shown signs of renewed strength. He has nibbled into his deficit. O’Brady experienced stiffness and pain in his neck on Thanksgiving, but he didn’t consider it serious. They are both sore, but remain uninjured, if not undaunted.

“A close friend of mine tragically lost his life attempting the same journey, and I can now appreciate what he went through,” Rudd said, referring to Henry Worsley, who died in 2016. “It is grueling, a different level to anything I’ve done before. So I kind of understand now what happened and why. It just takes so much out of you.”

O’Brady doesn’t disagree, but he’s also found an unexpected perspective.

“There’s something about the repetition and the monotony of the landscape that if you fight against it, if you start going ‘Oh, my God. I’m so lonely, I’m so cold,’” he added, “it seems like the anxiety can build quickly, but it can go the opposite way, too. I’ve been able to lock into some really deep, meditative, blissful states of mind.”