Redefining Freedom: What I Learned in Burma

Yoga International, Oct/Nov 2005 — Dropping into Yangon was like navigating the dreamscape between sleeping and waking. Our jet knifed through sheets of dusty haze that cleared just enough to give us a glimpse of something tangible: an expansive savannah, peasant fishermen angling in the wide mouth of the Irrawaddy River, groups of children playing on train tracks. I wasn’t quite sure what was real or imaginary. Maybe it was sleep deprivation from the 22-hour journey east. Or the shock that a land I’d always pictured as lush was bone dry. Perhaps I was simply overwhelmed that after years of hearing about the country’s violent military dictatorship and the big oil companies who have profited from the junta’s grisly tactics, I would finally walk on Burmese soil.

I closed my eyes and tried to fathom the suffering of the local elders who had endured colonialism, socialism, and now fascism. The closer we lurched toward the earth, the quicker my thoughts multiplied. But what never crossed my mind was this: everything I knew about freedom and suffering was about to change. Because that’s what Myanmar does to you. Then with a screech and a thud, we hit the tarmac and I opened my eyes.

Two visions had been burned into my brain—one of unthinkable pain and the other of mysterious beauty.

I first heard of Myanmar, or Burma as it was known until 1988, when I ran grassroots environmental campaigns in Los Angeles in the ’90s. I was the ultrapolitical angry young man who could—and often did—enumerate countless corporate affronts to people, plants, and animals at the drop of a hat, mostly at inopportune moments. It was a time in my life when deep breathing was generally confined to smoke breaks. But I met some well-intentioned, brilliant, and brave people along the way, including die-hard Burmese and American activists who worked closely with refugees on the Thai-Burmese border. Their message was consistent: the Myanmar government was one of the world’s worst.

The facts are irrefutable. Myanmar’s generals have confined democratically elected president, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung Sun Suu Kyi, to periodic house arrest for almost 20 years. They’ve inked generous deals for themselves with Total, Unocal, and Chevron- Texaco and have launched genocidal incursions into tribal lands that left thousands of orphans and amputees in their wake. Soon natural gas, plumbed from one of the world’s largest untapped reserves, will flow out of a nation where the working class still cooks on open wood fires, even in the major cities. And the generals have done this by obliterating any resistance.

Outspoken critics of the status quo are often taken from their homes in the wee hours and imprisoned for years. Some are never heard from again.

But my activist friends of the ’90s also raved about the sweetness of the Burmese people, their rich culture, and the gorgeous landscape. Two visions had been burned into my brain—one of unthinkable pain and the other of mysterious beauty. Fastforward to now—my political edge has been blunted by spiritual thirst and wanderlust, both of which were piqued by a recent invitation to join a cultural tour of Myanmar sponsored by Destinations & Adventures. I packed my well-worn duffle without a second thought, but as I landed in Asia and piled into a late model minivan at the airport, I had no idea which Myanmar I’d find.

But my activist friends of the ’90s also raved about the sweetness of the Burmese people, their rich culture, and the gorgeous landscape. Two visions had been burned into my brain—one of unthinkable pain and the other of mysterious beauty. Fastforward to now—my political edge has been blunted by spiritual thirst and wanderlust, both of which were piqued by a recent invitation to join a cultural tour of Myanmar sponsored by Destinations & Adventures. I packed my well-worn duffle without a second thought, but as I landed in Asia and piled into a late model minivan at the airport, I had no idea which Myanmar I’d find.

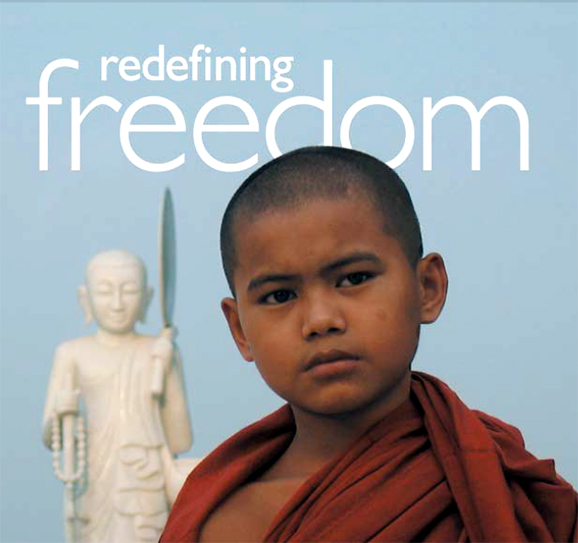

To be truthful, I expected to encounter a downtrodden population, a society in chains, and an intrusive and ubiquitous military presence. But Yangon (formerly Rangoon) turned out to be a laid-back city with a bustling urban core punctuated by roadside food stands and flocks of monks in saffron robes. It’s the kind of place where a 20-foot tall Revlon poster of Julianne Moore peers down from the side of a shopping mall across from a Buddhist shrine.

Jetlagged, our group arrived at Kyauk Taw Gyi Pagoda in West Yangon just before sunset. I left my sandals at the base of a long staircase and climbed barefoot toward an enormous statue of the Buddha on the temple plaza for a bird’s-eye view of the hot sprawling city below. I was surrounded in the dusky red light by hundreds of warm and joyful people, who seemed approachable, relaxed, and open. I was finally in the midst of it, and the place felt free. All my preconceptions evaporated as I watched families socializing, laughing, and praying; monks and nuns of all ages wandering the grounds; and young men in adjacent fields playing soccer and cane ball (an enthralling hybrid of volleyball and hackeysack). Vendors peddled beads, robes, and sandals; and clairvoyants offered fortunes on the cheap. Clandestine lovers kissed in the shadows.

Over the next two weeks I would learn that this bustle of social, spiritual, and commercial activity happened every day at pagodas all over the country. Buddhism in Burma, it seemed, had developed into something more than a spiritual path. It had taken on a life of its own and become a culture, a way of life.

The next day we flew to Shan State and boarded a van to the third-world Venice that is Inle Lake. As we bounced roughly over rutted roads, tailormade to shred shocks, our driver barreled through hairpin turns overlooking spectacular river gorges and sculptured rice paddies. Torn between nausea and awe, I managed to remember that according to the Buddha all things—including nerve-jangling car rides—are impermanent.

According to the Buddha’s first two Noble Truths, all is duhkka (suffering), and it is our attachment to people, places, things, ideas, and emotional states that produces suffering because these things are impermanent. This notion is ingrained in the Burmese psyche—nothing is permanent. And that’s why it’s common for Westerners (and even Burmese refugees living in America) to point to Buddhism as a pacifying influence, making it possible for the population to be controlled more easily. But the concept of impermanence can also be construed as a source of strength because it empowers people to remain hopeful and open-hearted in the face of tyranny.

In the midst of pain and upheaval, they had tapped into an eternal source of freedom, one that bubbles far below the arbitrary lines of politics or religion.

After three harrowing hours we arrived at Inle Lake and set off by canoe to explore. The place appeared to be frozen in time. Aside from the outboard motor propelling us through the green still water, the modern world was nowhere to be found.

The enormous lake (22 kilometers long and 11 kilometers wide) is framed by a series of inlet villages. There are 17 in all, and locals who live in the tiny teak houses set along the lakeshore on stilts make a living by spinning silk, fishing, and farming floating garden plots anchored to the lake floor—as they have for hundreds of years.

That night we stayed at Khin Nyunt, a gorgeous eco-retreat on the lake owned by Burmese hotelier U Ohn Maung. He had been among thousands of democracy advocates jailed in 1988–1989 when the junta took over, and I heard from him firsthand of the transformative and liberating power of vipassana meditation.

When Maung was released from prison, the democracy movement was in shambles, and many of his friends and comrades were missing or dead. So he went on a 30-day vipassana retreat and the experience, a common one in Myanmar, changed his life. Today, his political energies are channeled into service. He builds orphanages, hospitals, and schools. “Vipassana changes the way you react to the world,” he told me. “It gives you awareness of your emotions, and awareness is freedom.”

Later, as the sloshing water, exotic insects, and occasional owl conspired to lull me to sleep, Maung’s story stuck with me. Was his transformation simply an intelligent choice given the circumstances? Or had he really tapped into something deeper?

Ashin Kelasa, 39, splits his time between his Mandalay monastery and the rugged sierra in Shan State.

Our next stop was Mandalay, the heart of Buddhist culture in Myanmar. In a country teeming with stupas, pagodas, monasteries, meditation centers, and monks, no place has more than this former capital. From the top of Mandalay Hill scores of golden domes pierce the ever-present haze created by thousands of cooking fires. After two days of touring, I arrived at the Amarapura Mahagandayon Monastery, hoping to find someone who could elaborate on Maung’s experience. And as soon as I set foot on the cobblestone streets, Ashin Kelasa, a lanky 39-year-old monk in John Lennon glasses found me.

I told him about my encounter with Maung, and he led me to his room, a converted shrine where his “light body” diagrams and spiritual principles are tacked to the peeling white walls along with the New Year’s prayer for peace he mailed to President Bush. We sat cross-legged on the concrete floor, and he explained that the Buddha showed his followers how to break the cycle of suffering through insight, or vipassana, meditation. “Even Buddha experienced pain, but with awareness he could see it for what it really is, just a passing state,” said Kelasa with his trademark grin. “All you need to do is learn abroton (deep abdominal breathing), and sit silently. Then you will realize the truth and nothing else will matter.”

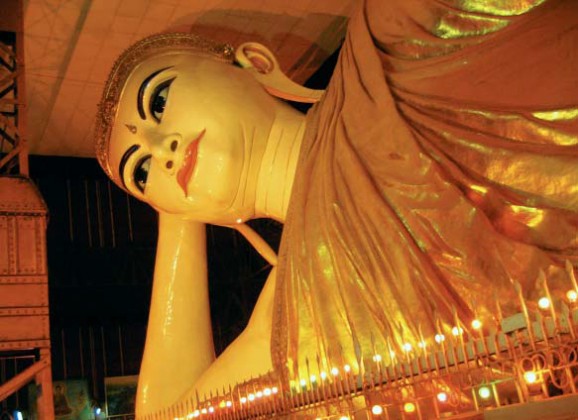

But visit any pagoda, and you will likely witness all sorts of religious rites but very little, if any, meditative practice. Take the ancient Mahamuni Pagoda, for example. It is the most revered temple in Mandalay. Inside it is perhaps one of the oldest Buddhist statues on earth, though its origins are up for debate. Some archaeologists believe it was cast in the 1st century CE, while devout worshippers consider it to be one of three remaining statues created when the Buddha was still alive 2,500 years ago. The statue was brought to Myanmar in the 12th century and placed at this site in 1784, where it has taken on mythic proportions. Pilgrims flock here from throughout Southeast Asia to smear gold leaf on its body—the gold is now at least 15 centimeters thick.

People stream in daily, hoping for blessings of health and abundance, while monks chant and chime bells and gongs, and drummers pound out ancient rhythms. While I was there a group of young children arrived in ceremonial dress to receive the blessing of initiation. After the blessing they are allowed to spend one week a year living in a monastery, where they learn chants and prayers, collect alms on the streets with older monks, and hear stories about the Buddha. But while the initiation ceremony was contagiously festive, and the pilgrims’ deep devotion was beautiful to watch, that doesn’t mean much in Kelasa’s eyes. Neither does the photo display of several nefarious government officials (dressed in military garb) visiting Mahamuni Pagoda with Myanmar’s top monks, or the “Men Only” sign at the Buddha’s foot. Women are not allowed to touch the statue and must meditate and pray in a fenced-in area 15 feet back.

When I spoke with Kelasa about all of this, I found he had no illusions about the stark difference between the “ism” of the Buddha—all the history, imagery, rites and rules, hierarchy, and manipulations— and the heart of the Buddha’s teachings themselves. “Kings build pagodas to show their piety, but the pagodas, the ritual, the statues, the music is not insight. It is not the truth,” Kelasa said. “Everything is the energy of matter and mind. There is no difference between man and woman, American and Burmese, or Christian and Buddhist. Vipassana meditation allows you to see this. And when you truly understand, and your mind stops clinging to notions of self and other, desire and loss, then you will reach nirvana. It can happen in one week or the next life.”

When I spoke with Kelasa about all of this, I found he had no illusions about the stark difference between the “ism” of the Buddha—all the history, imagery, rites and rules, hierarchy, and manipulations— and the heart of the Buddha’s teachings themselves. “Kings build pagodas to show their piety, but the pagodas, the ritual, the statues, the music is not insight. It is not the truth,” Kelasa said. “Everything is the energy of matter and mind. There is no difference between man and woman, American and Burmese, or Christian and Buddhist. Vipassana meditation allows you to see this. And when you truly understand, and your mind stops clinging to notions of self and other, desire and loss, then you will reach nirvana. It can happen in one week or the next life.”

Kelasa’s knowledge comes from experience. As a 20-year-old college student in 1988, a year of tremendous upheaval in Myanmar, his mind was clouded with grief over his mother’s death, and seething with anger toward the military machine that was crushing his people. While demonstrations erupted and were violently suppressed, he practiced insight meditation for the first time and connected to the practice immediately. Soon after, he became a monk and moved to the monastery, where he’s been a teacher for the past six years. He practices meditation for three hours every day and teaches for another three. He stopped short of discussing his own experience of enlightenment, but smiled and said, “Anyone can talk. But nirvana and vipassana are very difficult to talk about. You must practice. Then you will know.”

Still, this much was clear: in the midst of pain and upheaval, Kelasa, like Maung, had tapped into an eternal source of freedom, one that bubbles far below the arbitrary lines of politics or religion. Their transformations came from a personal practice that lifted them up from the depths of misery.

These days Kelasa comes and goes from the monastery at will. He prefers to live in the mountainous Shan State in northeastern Myanmar, where he teaches impoverished hill-tribe children to read and write, and counsels their parents. There are equally loving, altruistic monks throughout Myanmar.

While he may not have much use for religious pomp, circumstance, or hierarchy, Kelasa recognizes the importance of the sangha, the organized clergy of Buddhism that has become Myanmar’s de facto welfare system. In addition to young people who live at the monastery for one week a year, almost every monastery in the country cares for a few children whose parents are destitute. There is no social stigma associated with sending a child to the monastery. It’s considered a blessing that resident monks can feed, clothe, educate, and provide emotional support for the children.

In the wet season the landscape turns jade, contrasting sharply with the red brick and clay temples. I was there in the dry season, and it was hard to tell where the golden brown savannah ended and the temple foundations began.

In the wet season the landscape turns jade, contrasting sharply with the red brick and clay temples. I was there in the dry season, and it was hard to tell where the golden brown savannah ended and the temple foundations began.Just upriver from Mandalay, Bagan is known around the world as a must-see tourist destination. Archaeologists consider it, along with Angkor Wat in Cambodia, to be one of the most important cultural sites in Southeast Asia. To reach the abandoned city, our minivan rattled along sandy riverbanks that blended into fertile farmland that faded into scrub brush. We passed ox carts loaded with sugarcane, peanuts, and enormous casks of drinking water as they rolled down the rutted dirt roads. Thousands of ancient stupas and pagodas rose majestically above acacia trees, coconut palms, and an occasional lonely shack.

Inside the temples, washed-out murals depict Buddhist mythology, and the impressively detailed silver and bronze statues are as breathtaking as the sensational views from pagoda rooftops. That’s where I met 15-year-old Win Zaw Aung, who told me that in the wet season the landscape turns jade, contrasting sharply with the red brick and clay temples. I was there in the dry season, and it was hard to tell where the golden brown savannah ended and the temple foundations began.

Aung lived in a monastery with his cousin and brothers for four years. “We did chores, morning and evening prayers, and after lunch we studied reading and writing,” he said. He left the monastery after his father’s death to support his mother. Now he works in Bagan as a guide who lights the way for tourists as they climb the dark, narrow staircases in the 11th century temples dominating the landscape.

Aung longs to return to the monastery so he can continue his education. “I’m too poor to go to school,” he said, “and I miss learning.” He may get his chance because the government, under the guise of preserving the ancient pagodas, will soon open a modern viewing center, owned by one of the generals’ in-laws, where tourists will pay a fee to get a similar yet more removed view. Locals expect police patrols to crack down on small-time guides like Aung to prevent competition.

There are a million monks in Myanmar. If they were to rise up in unison and motivate the masses, the government would be powerless to stem the tide.

There are a million monks in Myanmar. If they were to rise up in unison and motivate the masses, the government would be powerless to stem the tide.And the people will likely accept their fate quietly, while an elite class grows wealthier and more powerful, and the monks remain silent. For all its altruism, it seems that the sangha does not know its own strength. There are a million monks in Myanmar. If they were to rise up in unison and motivate the masses, the government would be powerless to stem the tide. Kelasa was one of the few people who would talk openly about the meaning of freedom. And before I left Mandalay I asked him about the collective silence of the monks. He didn’t have the words to explain it.

One man who had seen monks get involved in politics was Aung Sun Suu Kyi’s charismatic civil attorney, 72-year-old Uko Mynn, who I met back in Yangon at the end of my tour. He was at the center of the action when a popular demonstration against the socialist government flared up in front of the U.S. embassy in 1988. “Monks took part, no doubt,” he said with pride.

It was a dramatic scene as 100,000 protestors marched toward an armed military squadron. “There were students, monks, intellectuals, all walks of life,” remembers Mynn. “In front was a monk carrying the traditional offerings for the last prayer before dying.

They were going right into the rifles. I was sure they were all about to die. But the army parted, and the demonstration went on. The next day there was an even bigger demonstration. This time there were 200,000 people, and the one-party system collapsed!”

This was Myanmar’s chance for democracy, but sadly, the generals formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and established martial law. They changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar, and elections weren’t held until 1990. All the while, demonstrations continued, but the SLORC met non-violent demonstrators with bullets and clubs. In one particularly bloody scene, several monks were shot and killed while shielding protestors. Suu Kyi won the 1990 election and a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1991, but the military has never relinquished power.

Through it all, however, the Burmese people remain remarkably optimistic. Most endure tremendous economic hardship and struggle to make ends meet, working in halfempty hotels and dusty lacquer factories, and doing hard labor—but they are not bitter. This was the message I got while visiting Myeat Khar Taw, a dirt-poor village on the outskirts of Bagan. Here, oxen are still used to grind peanut oil, families of five live in one-room shacks, and the wealthiest farmer in town earns $160 per year. The village has visitors, but it welcomed my group like old friends. The villagers prepared a delicious lunch; uniformed school children sang and practiced their English with us; and a local monk offered a prayer of loving-kindness. This place, which by Western standards should be completely depressed, overflowed with happiness and hope.

This place, which by Western standards should be completely depressed, overflows with happiness and hope.

This place, which by Western standards should be completely depressed, overflows with happiness and hope.The Buddha taught, “There are cares and troubles to be got rid of by endurance.” But that does not necessarily mean, as some may claim, that Burmese Buddhists are content to suffer. On the contrary, it could be argued that their cultural bent toward selfless service is in itself a political action. The Buddha understood that an individual’s ability to practice meditation and become liberated from the endless cycle of suffering depends on certain material and social conditions. So the sangha’s motivation to serve may not lie simply in a desire to assist impoverished people in times of need. As well as being a force in education and social welfare, the sangha also creates space for nurturing spiritual connections.

On the surface this may smack of quietism, but over time, if the people choose to practice meditation, teachers like Kelasa believe that they will no longer identify with either their suffering or ephemeral pleasures. They will have tasted a sense of freedom that cannot be legislated. Only by tapping into that everpresent, infinite communal Om that pervades all things will they be free.

Perhaps that’s why, even with the oppression that exists throughout this beautiful country, its people have such quick, easy smiles, such warmth, and such a strong, resilient spirit. As bad as conditions may get, they know their suffering won’t last forever and that true freedom is a personal journey. This is their source of hope.

You don’t need to be enlightened to feel it— hope courses through dusty villages where barefoot children sing the English alphabet. It bounces off the cobblestone streets of a Mandalay monastery; saturates orphanages, hospitals, and schools along Inle Lake; and flows from the heart of a pilgrim monk living in a shack on the Shan plateau. And it glows from the golden dome of Shwegadon Paya at sunset.

No trip to Myanmar is complete without a sunset trip to its greatest and oldest temple, Yangon’s 2,500-year-old Shwegadon Paya. An enormous solidgold stupa stands at its center, surrounded by dozens of shrines and pavilions where locals make offerings, meditate, and pray. As the sun descends, Shwegadon Paya lights up in whites, golds, and reds. Old monks in tattered robes lean on statues of the Buddha, devotees touch the Buddha’s heart and then their own. Dozens of candles burn at birthday shrines. Worshippers douse the statues with water to cleanse their own sins symbolically. A beautiful young woman’s chant echoes off the marble floors. The pavilion is alive with color, spirit, and mystery, just like Myanmar—a country plagued by systemic problems, but one that pulses with deep beauty.

On my last Myanmar evening I saw a telling sign that proves the tenuous nature of Myanmar’s governing elite. The stupa was covered in scaffolding to remove General Nyunt’s name from several golden tiles. Nyunt, the former Prime Minister and Chief of Military Intelligence, had been arrested by his cronies for suggesting “a road map to democracy.” Nobody knew what had happened to him. One day he was top dog, the next day he was gone.

Myriam Grest, Destinations & Adventures’ operations manager in Myanmar, shrugged knowingly and said, “Change can be just that quick here. Any day the rules can change; everything can change.”

And that’s why the old lawyer, Uko Mynn, still has faith in democracy. “The generals will fall,” Mynn assured me. “Although they have an iron fist, eventually it will split all on its own. Change will come from within.”