The Poke Paradox

I. The Poke Sampler

“When there’s a bowl of popcorn in the middle of the table, we think, I’m gonna eat two bites. Then we eat the whole bowl,” said Jennifer Bushman, founder of Route To Market and director of sustainability at the Bay Area seafood chain Pacific Catch. “That is human. That’s how we consume.”

Seconds later, we order the poke burger (among other things). Because of course we do.

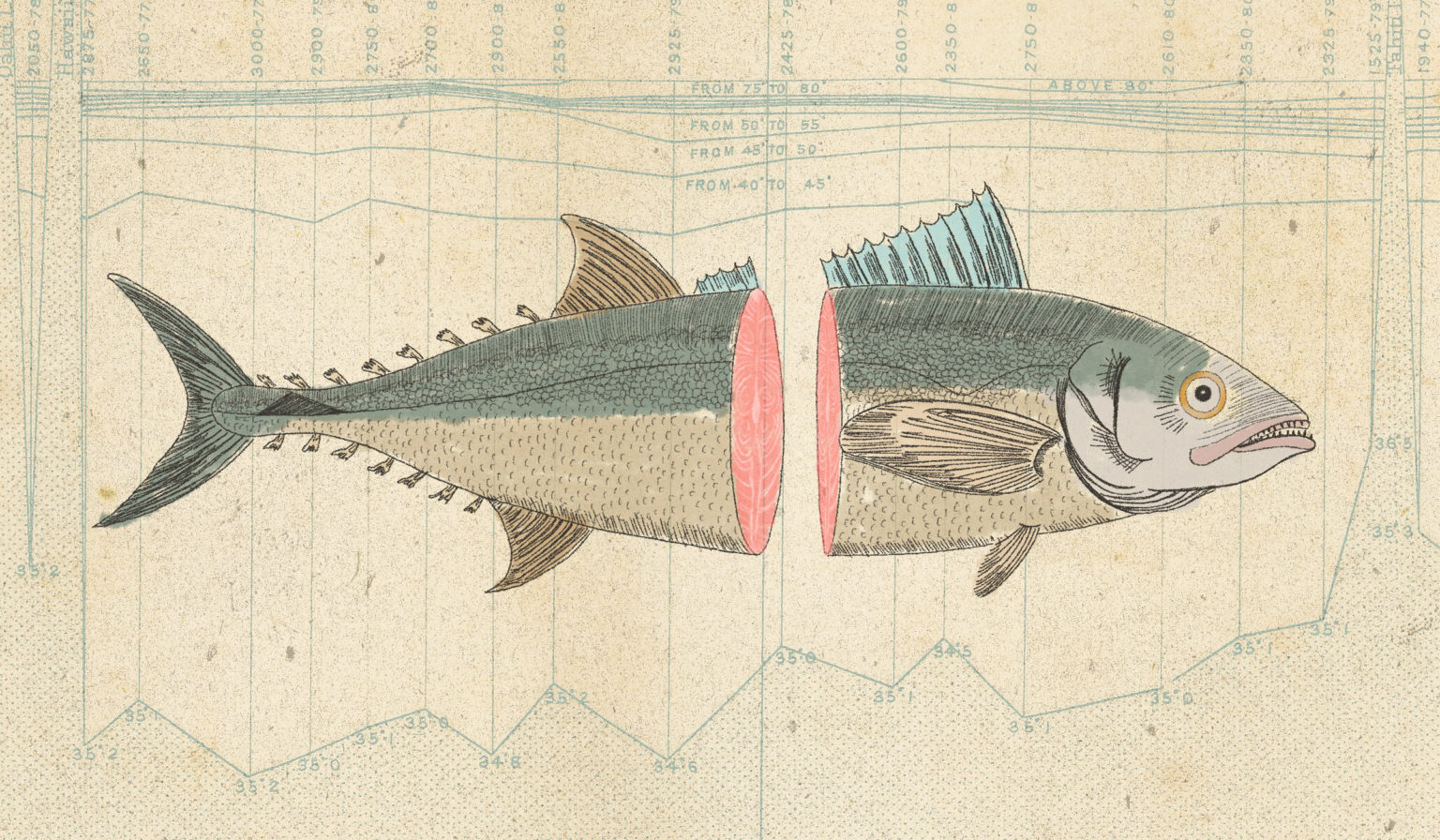

It had been a couple of weeks since I called Bushman to ask her about how Americans consume seafood, how that’s changing, and what it means for the fishes in the sea and the ocean itself. I needed to know if America’s recent love affair with poke (pronounced poh-keh), that tangy, sublime, umami-packed, raw Hawaiian seafood salad that has swept the nation, was in fact a problem. I was curious: Does poke drive an overharvest of certain fish species like yellowfin tuna? Does it enable the accidental bycatch of more charismatic marine life like turtles, dolphins, and sharks that get accidentally tangled in nets or hooked on long lines? Simply put, is poke a threat to the delicate ecology of the ocean, not to mention the ever-competitive commercial fishing industry? These are the issues that keep Bushman up at night, and she invited me to a long lunch at Pacific Catch in the Corte Madera Town Center to wrestle with them. Which is how I found myself in a tucked-away leather booth at an upscale Marin County shopping mall down the street from San Quentin State Prison.

Before all those mainland American poke joints sprouted like fields of poppies after a good rain, Pacific Catch, launched in 2002 by restaurateur Keith Cox, was one of the few places outside of Hawaii that served it. Their original 26-seat restaurant in San Francisco’s Marina District was inspired by a trip Cox took to Maui, where he fell in love with poke.

At the time few mainlanders knew what poke was. Cox and his team described it as a deconstructed sushi dish. The restaurant also served grilled fish and fish tacos, but poke was immediately its top-selling menu item, and it still is. Sourcing sustainably — only serving seafood that has been harvested with a minimum impact on the environment and the fish populations — has always been important to the brand, and shortly after opening their second restaurant, Cox flew to Oahu to make long-term deals for ahi (yellowfin tuna) caught by handline on day boats, rather than often problematic longline fishing boats. That was a good start, but as the years flew by, it became apparent that it wasn’t enough. In 2017 Cox asked Bushman to make their menu 100 percent sustainable.

She relies on nonprofit, third-party certification programs like Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), and Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) — the latter two launched by the World Wildlife Fund. Mahi-mahi, a fish taco staple, was overfished and mostly red rated (meaning avoid) by Seafood Watch when she took the Pacific Catch gig, so Bushman nixed it in favor of rockfish sourced from a sustainable local fishery in Northern California. She also uses the James Beard Smart Catch portal to research fisheries and fish farms. Smart Catch was created to help chefs with sourcing, Bushman says, but at Pacific Catch, where everything is now yellow (good) or green (best choice) rated by Seafood Watch, she does that heavy lifting for all the restaurants. She orders 500,000 pounds of fish each year and can be demanding with distributors.

“Imagine a chef in a single restaurant who’s super busy. The fish comes in and it looks good. The eyes are clear, the gills are bright red, it’s nice and firm and the scales look good. He’s like, great, I’m good to go, but seafood changes hands more times than any other food and beverage commodity in the world. On average eight to nine times. So I’m saying to my distributor partner, what the heck? Where does it come from? How was it caught? Where are the certificates? Imagine a chef needing to do that?” Or, say, the owner of a fast-casual poke bar where a bowl of raw fish and rice costs about 10 bucks.

These kinds of questions matter because Americans are eating more seafood than we have in years, and though we have some of the best-managed fisheries on the planet, 62-65% of the seafood on the American plate is imported — most of it from Asia where fishery management can be lax or even nonexistent — which is frightening because according to a 2018 report published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 33% of the world’s fisheries are overfished (meaning they are in danger of being fished out), and 57% are fished to their absolute maximum capacity. Bushman is explaining this to me as our server arrives with the poke sampler, and though the words “fished out” are still ringing in my ears, it does look delicious, and this batch is certified sustainable.

Our first bite is the original Pacific Catch recipe and a take on what most mainland poke restaurants consider the classic Hawaiian dish. Here is cubed ahi, marinated in sesame oil and shoyu (a Japanese-style soy sauce), and tossed with sweet onion and a hint of chile. The ahi we’re eating, Bushman explains, is yellowfin tuna caught by handline at a small scale, certified fair trade fishery off remote Buru Island in the Maluku archipelago of Indonesia, which isn’t exactly down the street. “It comes in frozen and already cubed, on container ships,” she says.

Not long ago such gritty details were kept secret, and depending on the distributor and where they source their fish, often still are, but thanks to robust certification programs launched by nonprofits like Monterey Bay Aquarium and WWF, which require regular third-party audits, the seafood supply chain is becoming demystified. That’s led to greater consumer awareness and increased customer demand for even more transparency. Bushman doesn’t just embrace that, she also promotes it. After all, almost all raw tuna served in the U.S. arrives frozen, not fresh, so what’s the point in pretending otherwise? The container ship allows for a smaller carbon footprint than air freight, another aspect of the business tracked by Bushman, who is helping to strip the secrecy and shame from the seafood business.

As for the poke, the ahi is soft to the tooth. Not too firm but not gelatinous either, and unlike most poke bars, the Pacific Catch version is marinated, not just sauced. There is acid, there is heat, and though the fish came from far off, it tastes clean, without a hint of fishiness.

Simply put, is poke a threat to the delicate ecology of the ocean, not to mention the ever-competitive commercial fishing industry?

Next we try the serrano ahi, which is a version of spicy tuna, a popular incarnation that as usual offers too much mayo for me. The salmon avocado poke, best sampled on the back of a wonton chip, features house-cured Verlasso salmon (sourced from a sustainably certified fish farm in Chile), tossed with chunks of California avocado, toasted shallot oil, scallions, lemon, and crispy shallots. But the citrus kanpachi is the true revelation.

Kanpachi is a farmed yellowtail, a hamachi alternative, and the variation served at Pacific Catch was grown and raised from an egg at Blue Ocean Mariculture, the only offshore fish farm in the United States. The poke, I must confess, is not my favorite flavor. There’s too much going on, what with the orange and yuzu, pomegranate, ginger, mint, and crispy quinoa, but the fish snaps to the tooth like the best red snapper sushi, and I want more of it, mostly because it isn’t salmon and it isn’t tuna.

Salmon and tuna are the two most plated fin fish on earth. The majority of salmon we eat is farmed, and though nearly one third of global salmon farms now have some sustainability certification, the biggest operations, such as Mowi in Scotland, Cermaq in British Columbia, and AgroSuper in Chile, have enormous environmental footprints and have been linked to coastal pollution problems, stemming from too much fish waste and an overuse of pesticides and other chemicals. Ahi tuna, meanwhile, is the most sought after wild fish in the sea.

There are 4.6 million fishing boats on the water worldwide; 3.5 million of them, or 75 percent of the global fleet, are in Asia, and most are searching for tuna. Nearly 5 million tons of tuna were harvested from the ocean in 2015, and based on recent estimates, nearly one fifth of it comes from fisheries exploited at a level that could cause their stocks to collapse unless something changes. Modern-day poke is synonymous with ahi, the Hawaiian word for tuna, which is why, according to Bushman, a lot of it cannot be considered environmentally sustainable.

“Is there too much poke?” I ask between bites.

“Probably,” Bushman says. “Poke is the new fish and chips.”

That’s when the poke burger arrives, and there it is again. That conspicuous warm-blooded, ruby-fleshed, silver-scaled, yellow-finned beauty, chopped and shaped into a patty, marinated in sesame-shoyu, seared to perfection, and nestled on a black sesame bun where it’s been crowned with avocado and tangy layers of pickled ginger. The fact that such an indulgence exists has to be proof that six years into its rise and reign, we remain witnesses to the age of poke. A disciplined Bushman cuts but a sliver to enjoy. I do the same at first … but you know how humans consume. Poke burger does not live long.

***

Poke means cut or slice in Hawaiian, and it’s a dish easy to love. A great bowl of poke tastes as wild and fresh as the sea itself. If cold Corona and lime is a sandy beach, poke is a tropical island. It is a culinary portal to the world’s most remote island chain, and now thanks to globalization and copycat culture it is currently served in nearly every major city in America.

Poke means cut or slice in Hawaiian, and it’s a dish easy to love. A great bowl of poke tastes as wild and fresh as the sea itself.

“It was Hawaii’s comfort food for many years,” says Hawaiian chef Nakoa Pabre, but ahi wasn’t always the central ingredient. In fact, most early Hawaiians didn’t hunt ahi very often, if at all. They fished in small canoes — with so many fish near shore there was no need to venture outside the reef where ahi roam — and they never sauced their catch. “Super early days, it was made with the scrap pieces of reef fish, and the poke was really simple. It was Hawaiian salt, which dried naturally on the rocks, roasted kukui nuts (a wild nut), and seaweed, all different kinds of seaweed.”

Beginning in the late 19th century, Japanese people began moving to Hawaii to work pineapple plantations and they brought sesame oil and shoyu with them. “Now aioli is the big thing,” Pabre says, “so a lot of people make spicy tuna.”

In 2007, when Pabre opened Da Poke Shack, his first restaurant in Kona, poke wasn’t yet a mainland sensation, but its moment was coming. By 2012 it had gained a mainland foothold, thanks to Hawaiians who brought it with them to the West Coast, Salt Lake City, and Las Vegas. In 2014, according to FourSquare data first reported by Eater, there were already 342 poke venues nationwide. In 2016 there were 700. Although there are reports that the trend has faded, thanks to a spate of closures and bankruptcies, in July 2019 there were 2,004 poke restaurants open for business and listed on Yelp, spread across 47 states plus the District of Columbia. That doesn’t even include every restaurant with a poke dish on the menu (like most Red Lobster and Cheesecake Factory kitchens, hundreds if not thousands of sushi bars, and several National Park lodge dining rooms).

West Virginia and South Dakota are the only poke-free holdouts, and like in a more familiar institution, the electoral college, Florida (148), New York (157), Texas (155), and California (691) deliver the big numbers.

Oh, and the names. There’s a long list of poke joints that are actually mispronouncing and/or misspelling their main dish. Here’s looking at you, Okie Pokie, Hoki Poki, PokiRito, Pokay, and Bespoki. Poke Me, I honestly don’t know what to do with you.

At this point, however, the most notorious name of all is Aloha Poke Co., a Chicago-based chain that not only trademarked “Aloha Poke,” they reportedly sent cease-and-desist letters to restaurants who use “Aloha Poke” in their name or on their menu without their permission, which predictably outraged Native Hawaiians and many others who accused the chain of cultural appropriation. At least one Hawaiian-owned poke shop in Anchorage Alaska was forced to change its name.

II. Fast & Casual

Sweetfin, a Los Angeles chain in early on the poke tide, serves as an interesting case study on how and why poke took off. It’s cofounder, Seth Cohen, was 26 in 2013, when he quit his steady real estate finance gig to open a restaurant. But what kind of restaurant exactly? He needed the right concept, something scalable.

By then two important factors had altered the food and beverage landscape. First, the advent of grocery store sushi, specifically the Whole Foods sushi bar model, helped Southern Californians begin to trust inexpensive raw fish. Second, thanks to the nationwide success of Chipotle, where a gourmet chef created a burrito and taco concept in which everything was prepared in house, a host of similar fast casual dining spots found success in the L.A. area. Chains like Lemonade, Sweetgreen, Mendocino Farms, and Tender Greens offered healthy and delicious lunch options at an affordable price. Cohen and his partners, Alan Nathan and Brett Nestadt, began brainstorming their own fast casual start-up.

A big advantage in launching a poke shop is the lack of a commercial hood vent for the kitchen, one of the biggest sunk costs restaurateurs face and something that prices in the tens of thousands for even a small kitchen when permitting and insurance are factored in. Cohen loved raw fish, and he knew that outside Whole Foods the best options for sushi generally cost about $60 per person for a meal. Then he thought about poke, a dish he first enjoyed in Hawaii and had tasted again a handful of times as a small appetizer on the mainland. A poke bar wouldn’t need a hood, he thought. “I guess, as an entrepreneur I saw a market opportunity with a food I like to eat,” he says.

Cohen and his partners joined forces with chef Dakota Weiss to create a menu. That was the easy part. It proved much harder to find investment. The original plan was to raise enough money for one store, prove the concept, then expand, but they got no bites, so they put up their own money and opened in 2015. From day one there were lines around the block.

“We are a scratch kitchen,” Cohen says. “Every last thing we sell at Sweetfin, we make. We ferment our own hot sauce, we make our own ponzu, we make our own taro chips.” Which is promising to hear because as he recounts the early days of his business when he, Weiss, and staff worked every day for three months straight, I’m sitting across from him, eyeballing my own Sweetfin poke bowl. “We took that approach to make this a chef-driven experience.”

Eventually, we get around to eating. I’d ordered their classic tuna bowl, which was sauced to order with a sesame-shoyu mix and topped with avocado, crispy onions, sweet onion, and togarashi. It tasted fine, but there wasn’t a lot of flavor to the ahi, and that’s both because the fish wasn’t marinated (mainland poke bars can’t afford to marinate fish because they may end up having to trash whatever doesn’t sell on a given day) and because the tuna we eat on the mainland — including the ahi served in high end sushi bars — usually comes in frozen, which means it won’t taste fishy, but it generally isn’t all that flavorful either. Chefs I spoke with compared it to chicken breast. It’s more a blank canvass to be sauced than a true delicacy on its own.

Cohen went with an albacore Katsuji bowl, a collaboration with Top Chef star Katsuji Tanabe. Sweetfin has promoted chef collaborations since launch, and this fusion poke was dressed in a traditional Mexican peanut salsa called matcha, and topped with roasted corn, cilantro, and jade pearls of wasabi tobiko (fish eggs).

“You gotta try this,” Cohen says between bites. I scooped a bamboo sporkful, and he was right. It was delicious, full of bold flavor; evidence that when you go to a chef-driven restaurant you should allow yourself to be chef-driven, yet the umami was in the mix, not the fish.

Sweetfin has always offered salmon, ahi, and albacore. These days their salmon is raised in pens in the open water around the Faroe Islands and is certified sustainable. The albacore comes from a sustainably rated fishery in Fiji, and their ahi is a yellowfin tuna coming from yellow or green-rated fisheries, caught by either handline or longline depending upon the season. That’s a lot better than most mainland poke shops. While researching this story I approached or called more than a dozen poke bars to survey their sourcing. Staffers offered either vague answers (“Our tuna is from the South Pacific Ocean”), gave me a name of a scary big megadistributor, or simply had no clue.

“There are cheaper options,” Cohen says, “but I think you can taste the difference, and our customers do care that we do it the right way.” Early on, Sweetfin also offered a snapper from New Zealand and once had the same kanpachi on the menu that I tried at Pacific Catch, but they couldn’t move it because it was unfamiliar and cost a bit more. “Quality, sustainability, price, value,” Cohen says, “is a difficult equation to master.”

Cohen calls Sweetfin, which now has 10 shops in and around L.A. and San Diego, a celebration of L.A. sushi culture. They highlight Japanese ingredients common in sushi like togarashi (a red pepper spice blend), wasabi furikake (dried fish, seaweed, salt, and sesame), and yuzu kosho (citrus zest, garlic, chile, and salt). “We’re never going to be traditional. We’re never going to be able to compete with the guys who are going out in Hawaii that are fishing in the morning, bringing it in, cutting it up,” he says. “I mean, that’s just not possible at scale.” That was all explained in the story, that at the time of our interview (and until recently) was printed on the back of the menu. The last line read, “This is not your grandmother’s poke.”

Of course, in Hawaii, nine times out of 10 it is the uncles and grandfathers who make poke.

III. The O.G.

“You have good poke hands,” Nakoa Pabre says over the metallic clank of his spoon against the mixing bowl. “That’s what they told me when I was a kid, but nowadays you cannot use your hands.” Certainly not in a restaurant, and that’s where we are, in the dining room at Umekes, Pabre’s popular fish house in Kona. It’s still morning, the place is closed, but staff and Pabre’s cousin Mike are in the kitchen breaking down fresh fish, and between urgent calls and texts, Pabre talks story and mixes poke.

“My uncle had a big boat and he’d bring in 15,000 pounds at a time,” says Pabre, who was often recruited to help prepare for family luaus. “I remember being 6, 7 years old and having to clean and cut the fish, help the uncles prepare all the food. You know, cooking and making poke.” In 2007 he opened Da Poke Shack with a partner in Kona, and much like the Sweetfin guys, and Keith Cox at Pacific Catch, he framed his speciality in terms mainlanders could understand. “I called it a poke-sushi fusion, and it became very popular. Instead of it being a side dish, poke became the complete meal.”

‘My uncle had a big boat and he’d bring in 15,000 pounds at a time,’ says Pabre, who was often recruited to help prepare for family luaus. ‘I remember being 6, 7 years old and having to clean and cut the fish, help the uncles prepare all the food. You know, cooking and making poke.’

He left the business to start Umekes in 2015, where he expanded on his poke menu. He grills fish and steaks and cooks up old-school Hawaiian soul food, including a homestyle tripe stew that brings in elders from around the island. Almost all the produce and 100 percent of the beef and fish are sourced locally — a difference you can taste in his poke.

He offers me a cube of unseasoned, locally caught ahi, and after tasting so much bland tuna on the mainland, it was a revelation; all water and iron, ocean and blood. The fish was caught two days earlier, placed on ice overnight, and broken down into cubes by his kitchen team the very next morning. My mouth rang with that refreshing metallic tang that reminded me of drinking water directly from a hose as a kid on a hot summer day, and that was just a precursor to the house specialty poke, listed on the menu as the Hawaiian, but something Pabre lovingly refers to as the O.G.

It’s a dry rub poke, a throwback to the ancestral recipe, with hand-cut ahi rubbed in Hawaiian sea salt, chili flakes, and ground kukui nut, then tossed with a variety of local seaweed. It’s a simple dish with distinct flavors. The tuna had a salty crunch and was so moist there was no need for any sauce. The blanched seaweed brought a bold earthiness. Too often when you’re eating a poke bowl on the mainland there is just one big flavor. I want to savor Pabre’s mix.

While I’m awash in poke reverie, Pabre takes a call from one of the fishermen he works with and heads for the back door. When he returns he’s carrying an industrial-size cooler. “We call this thing the tuna hearse,” he says. Inside are two 120-pound ahi, caught the night before that had landed in Kona before dawn. He lifts one up by the tail. It’s a beautiful beast, one of the great nomadic hunters in the sea, and about five feet long from nose to tail.

Pabre has benefited from the poke boom. He’s consulted with shops in New Jersey and Germany, and he is proud to see Hawaii’s comfort food go mainstream, but he’s not a big fan of what he calls “the Subway model” of poke.

“There’s no love, no aloha,” he says. “I’ve tried many of them. With some of the bigger chains, the cubes are all the same cut because they are machine cut. We’re cutting the fish, sometimes gathering the fish, so there’s a lot going into it, knowing the measures it took to get to your bowl. I think that’s why mainland poke is mainland poke. They get in this frozen product, and just have to cut open the bag and top it off with all kine stuff.”

Pabre never uses frozen or imported ahi in his kitchen. “It’s all local,” he says. “Sometimes we barely make it through the day, but I’d rather not have it available and use other fish if I have to.” Many restaurants that serve poke in Hawaii, however, do import ahi.

He offers me a cube of unseasoned, locally caught ahi, and after tasting so much bland tuna on the mainland, it was a revelation; all water and iron, ocean and blood.

I visited the islands during the summer, right in the middle of tuna season, when the big schools swim south from Kauai, hit Oahu, and charge southwest past Molokai and Maui before reaching the waters around the Big Island. Yellowfin tuna are among the fastest swimmers in the sea (they reach speeds of up to 50 miles per hour) and are built like torpedos. When the thick schools come through in waves, fresh ahi is plentiful, but it’s also a migratory species, known to cross oceans, and when the big migratory schools swim away during the winter months, some of the ahi served in Hawaii is imported. Even during peak yellowfin season, some Hawaiian fishermen have noticed how much more difficult it is to land big yellowfin tuna than it used to be.

***

The Suisan Fish Market in Hilo is another must-try destination for poke on the Big Island. Founded in 1907 by Japanese fishermen (suisan is Japanese for water merchants), during World War II the business was threatened by a law that forbade fishermen of Japanese descent from launching their boats. Japanese families had been living in the area for 60 years by then, and their Hawaiian neighbors stepped up to keep the market alive.

Ever since, Suisan has maintained a roster of between 150 and 180 local commercial fishermen who operate from small boats in the waters around Hilo. I meet two of them, Hisashi Hose, 56, and Roger Antonio, 70, on the Suisan dock before dawn on a June Saturday. They’ve both been in the business for decades and I ask them if it’s harder to catch fish now than it was 30 years ago.

“Yeah,” Hose says. “It’s harder.”

“Before days you go out there you catch 20 pieces one night,” Antonio adds. “Nowadays if you catch five you’re the top dog. It’s changed that much. And the fish were bigger.”

“The fish are 100-pound size; 100, 120,” Hose says. When I saw a fish that big at Umekes it impressed me, but Hose insists they can get much bigger. “Before the yellowfin, 160, 200s. 200s would be all the time.” In fact, yellowfin tuna can grow as big as 400 pounds.

“The local longline industry has had a big impact,” says Suisan market manager Robert Shibata. “Tuna come into Hawaii to do their breeding because of the [water] temperature. Longliners journey 30 miles plus out and get that fish before it can reach Hawaii, and they’re capturing a bulk tonnage, so it’s taking away from that breeding aspect, hurting us sustainably. Now, the fish that do make it closer to our islands. That’s our local fishermen’s opportunity. That’s how they make their money.”

The Hawaiian longline industry problems don’t end there. It’s been plagued by accusations of inhumane work and living conditions for the migrant laborers — most of which are from Southeast Asia. Although recent innovation in longline fishing have reduced bycatch (and eventual death) of sharks, turtles, and marine mammals, those problems remain rampant in some territories. That’s what happens when you cast a five-mile longline, strung with thousands of hooks or bolts, and why Seafood Watch has given just one longline fishery a yellow rating. All others are red rated.

Even a business as old and storied as Suisan hasn’t been immune to the poke craze. Today it amounts to 50 percent of their entire retail business. Their exquisite poke case includes the sesame-shoyu “classic,” a spicy tuna, and a minimalist traditional Hawaiian recipe similar to the O.G. Shibata uses a grade of tuna just below sashimi grade for poke, and his chefs marinate each recipe for a couple of hours, at least. This is not the quick-sauced mainland version. Suisan delivers the real deal, but the more I learn about ahi and where it comes from, the more conflicted I feel. Which is why, even though it’s peak yellowfin season and the fish in Suisan’s case has been captured by local guys like Hose and Antonio, I gravitate toward less sought-after fish. It’s time to wean my palate off ahi.

Shibata offers me a bite of what he calls a mixed plate, a local winner, featuring the opihi, a Hawaiian limpet (think abalone) with an in-your-face uni-like funk. I also love the chi-hu, an ono poke, mixed with sea asparagus in a spicy Korean marinade. But there is one fish found in the blue water just off the coast of the Big Island that Suisan does not yet sell. Pabre does. It’s the Hawaiian kanpachi, a farmed fish I first tried at Pacific Catch then again at Umekes that’s beginning to captivate chefs across the United States.

“It’s a stellar product no doubt,” Pabre says. “Raw, cooked, grilled, it’s an excellent fish. We serve a ton of it.”

Blue Ocean Mariculture, the company behind Hawaiian kanpachi, is part of the new wave of commercial aquaculture projects, often helmed by young entrepreneurs or those with an environmental ethos. When Tyler Korte, a former teacher with a background in ecology, took over project management duties in 2015, Blue Ocean Mariculture had only one working fish pen and three others in need of complete reconstruction. Thanks to Korte and his team, things are a lot different now.

While in Hawaii, I visit what has become the only offshore fish farm in U.S federal waters. A short boat ride from the harbor and set roughly a third of a mile off the Kona coast are a grid of five cages held in place by 26 anchors and submerged in depths between 30 and 130 feet. Korte and I jump in, take a breath, and dive down 30 feet in water so blue it’s almost purple to inspect the wire netting. More than once, I press up close and the fish, a relative of the wild Kohala fish, striped like zebras, swirl in a schooling column. All of them were raised from eggs and hatched in tanks onshore.

Stinging sea lice can be an issue with salmon farms, but there is nothing like that around these pens, though they do receive looky-loos including oceanic whitetip sharks, tiger sharks, whale sharks, and mantas. We hope to see big sharks, because Korte and I are weird like that, but our only visitor is a curious bottlenose dolphin. Still, no matter who or what turns up they can’t get to the kanpachi.

The big advancement that has enabled a proliferation of more sustainable aquaculture in the past decade has been in fish feed. Instead of exclusively using a huge volume of wild-caught sardines, anchovies, and other feeder fish that marine mammals rely on to feed farmed species, these new operations use tailings or fish oils from canneries, often combining them with algae and yeasts to create a feed that delivers even more of the vital Omega-3 fatty acids fish need to grow and proliferate than they would get if all they ate were wild bait fish, which are captured by purse seine nets and often harvested in unsustainable numbers. Verlasso salmon, a product Jennifer Bushman helped launch, was the first salmon operation to innovate with fish feed. Verlasso set a new industry standard others have matched or exceeded.

However, while salmon — which is farmed all over the world with varying degrees of environmental stewardship — is not a true tuna alternative, kanpachi might be. It has the flavor profile of yellowtail with a pinkish flesh, and it’s terrific raw. But for many years farmed fish has been dismissed as inferior, thanks to mismanaged legacy salmon farms that damaged local stocks, polluted bays and coastlines with effluent (fish poop), and relied on antibiotics, pesticides (to combat sea lice), and too much wild fish to bring their product to market. That bad reputation is one reason that before Blue Ocean Mariculture, there were no offshore fish farms in U.S. federal waters. But that old story has begun to change thanks to chefs who appreciate the consistency in flavor of sustainably farmed fish, which comes with controlling what fish eat.

The Kona Coast of Hawaii, it turns out, is the perfect nursery for a scalable tuna or yellowtail alternative. Aquaculture is ancestral in Hawaii, where fishponds were common for generations. Economically and environmentally it meets the state’s goals too. “They want sustainability, they want food security, and they want another income other than tourism,” Korte says as we towel off on his work boat. “We’ve kind of hit all those tick marks for the state which has helped them to say yeah, we want this industry here.”

But it’s the perfect combination of deep water close to shore and a dependable current that make it work. Even on calm days the current is moving at least one knot. That’s enough to carry away any and all effluent the fish release.

“We’ve had to do a lot proof of concept,” Korte says. “We take water quality data monthly. Through that data we’ve showed we could put a lot more [fish] out here.”

The primary drivers for investment in aquaculture and to make the industry more environmentally sustainable isn’t to produce an ahi alternative, however. It’s the fact that by 2050 we will have a projected 10 billion people on the planet, and it requires about 40 percent less food to raise a pound of fish than a pound of chicken, and a tiny fraction of what it takes to raise a pound of pork or beef. And according to a recent study conducted by UCSB professor Halley Froehlich, a surface area the size of Lake Michigan is enough space to sustainably raise the same amount of fish (by weight) that we pull wild from the world’s oceans each year.

That doesn’t mean it’s easy to do the right thing. On our way back to the harbor, the main Blue Ocean working vessel, the one with the day’s kanpachi harvest, loses an engine and its captain can’t get into port. Korte hops aboard and coaxes her in, but it takes so long that it complicates transport to the fish processing plant down the road. From there, the kanpachi is shipped to other islands and the mainland aboard commercial flights to keep their greenhouse gas footprint down.

The open ocean, old boats, hatcheries, captive fish populations, flight schedules, wealthy investors, nothing about that matrix is predictable or convenient, and the seven-day workweeks aren’t an easy burden either, but Korte remains optimistic about both Hawaiian kanpachi and aquaculture in general.

“It’s a tough business,” Korte says. “There’s good potential in it, but most of the people I’ve met in this industry are not just doing this because they’re capitalists and want to make a lot of money. They have a love of the ocean and they want to do everything the right way. They want to move toward a sustainable [future] and they think aquaculture is a good solution for it.”

IV. PBP: Plant-Based Poke

But even if aquaculture evolves into the gourmet, multi-trophic fantasy some advocates dream of, where ropes of plump mussels and oysters are draped on the side of fish pens, getting fat off fish poop, thus filtering the water alongside strands of carbon-slurping kelp, market realities exist, and if people keep salivating for ahi, fishermen will find it by any means necessary. Some of them illegally. In fact China and EU member states are among the countries that subsidize fuel for commercial fishermen. In a recent report, researchers from the University of British Columbia claim those subsidies enable illegal fishing in international waters. Even those with legal clearance are often armed with longlines or destructive purse seine nets that let nothing escape. And once it’s caught, of course, restaurants will continue to serve it.

So if you crave poke and aren’t in Hawaii during peak yellowfin season, ask questions, and if the server or chef has a clear read on where the fish is coming from and how it’s caught, thank them, says Ryan Bigelow of Seafood Watch.

“You can’t be sure every dish of seafood you eat will be sustainable,” Bigelow says from his office in the Monterey Bay Aquarium. “But no one person is going to save the ocean or ruin it in a day. Your strength is your voice, so don’t be afraid to ask questions.” No matter what the answer is, the question has power, Bigelow argues, and like growing market demand for sustainable seafood, there’s always a chance that it may ripple up to the chef and out to the supply chain.

Before we parted ways at Sweetfin, Seth Cohen mentioned that his salmon sales are up and ahi orders declining, but he was most excited about the growing demand for his plant-based poke bowls, which now account for 20 percent of his business. After returning to L.A., I try a couple of them. The miso eggplant and mushroom version is sauced in sesame-shoyu and features slim Japanese eggplants sautéed to melt in your mouth and delicate shimeji mushrooms that offer an al dente crunch. The sweet and spicy ponzu lime sweet potato bowl, featuring steamed sweet potatoes and studded with edamame, had more kick, however, thanks to serrano chiles. Both have me plotting my return.

“Part of me wants to take tuna off the menu just to see what happens, but it just doesn’t work for this,” Cohen says. “If you’re going to eat tuna once a week I think that’s OK. It’s all about moderation.”

Related articles

Contributor To

Subscribe to my newsletter

Sign up for occasional updates on new stories, book releases, and behind-the-scenes writing insights - straight from Adam. No noise, just good writing.