The Spice of Life

Nutmeg trees and coral reefs abound in the Banda Islands. On the trail of colonial invaders — and wild dolphins — Adam Skolnick discovers how these Indonesian islands helped birth the modern world.

Travel and Leisure Asia, October 2012 — Photographed by Foued Kaddachi.

Abba was humming again. It was his happy affliction. I heard it when he was asleep in our shared second-class cabin onboard the Pelni ship from Ambon, once more when we endured a near-lethal disembarkation scrum, and again when Abba, a 37-year-old Banda native, hotel operator and tour guide, led me and four others into Benteng Belgica, a hulking fort built in 1611 by Dutch colonists greedy for nutmeg. We followed him past mossy iron cannons strewn in the courtyard and into the dank prison, where his tune pinged off thick stonewalls and washed over a tiny clutch of fruit bats napping on the ceiling.

“This is where the Dutch put the Bandanese when they traded their nutmeg with the English,” he said between melodies. “Back then nutmeg was worth more than gold.”

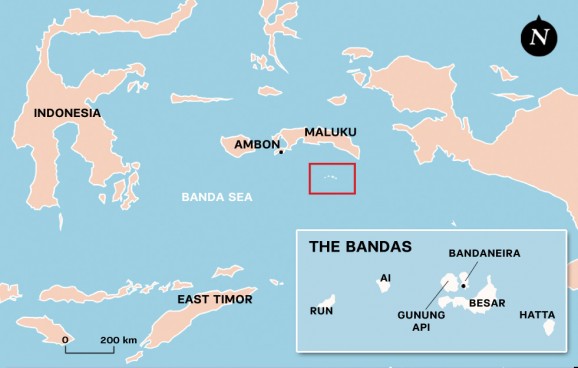

Back then, the Banda islands were the only source of nutmeg in the world. Prized by 16th- and 17th-century Europeans for its natural healing properties, and declared a cure for everything from the common cold to flatulence to the plague, the spice propelled this baby archipelago, in present-day eastern Indonesia, from anonymity to supremacy on the working maps of Western kings.

The hunt for nutmeg and cloves, which then only grew here and in Ternate and Tidore, in present-day Maluku, lured Columbus on his accidental journey to the West Indies in 1492. Though the Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach this remote sprinkling of rock, lava and sand, it was the Dutch who conquered the Bandas, and battled for half a century with the British for the nutmeg trade monopoly—until April of 1667 when the English crown gave up, trading their tiny, windswept island of Run to the Dutch in exchange for New Amsterdam (that is, Manhattan).

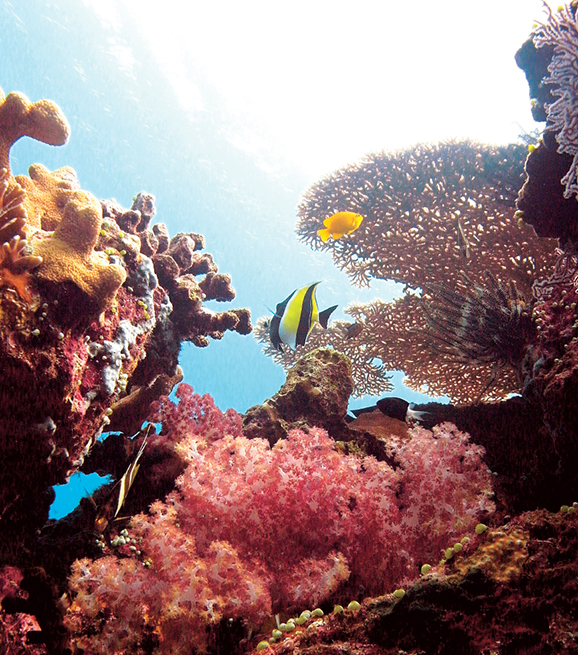

The Bandas helped shape the modern world; their Dutch colonizers reshaped the local population, killing or exiling the vast majority of the Bandanese. Sailing into the archipelago in 2012, it’s hard to believe such a small tropical cluster could have held that much sway. And it seems incongruous to witness a Banda native like Abba hum his way through an account of that brutal history. But no matter where you wander here, you’ll be greeted by warmhearted locals who still rely primarily on spices and fish for subsistence; you’ll find fascinating relics of the region’s past flaking in the tropical sun; and, if you don’t dive, you’ll want to get your certification as soon as you see the powdery white-sand beaches and aquamarine seas full of sunken shipwrecks and rich coral reefs. These remote islands overflow with natural and historical glories.

Bandaneira is the islands’ access point, and it’s also the best place to explore Bandanese history, with countless old colonial structures in various states of restoration (read: disrepair).

A light rain began to fall as we exited the prison and scaled a rusted ladder with razor-thin rungs to one of the fort’s five turrets. Here was a 270-degree view of Bandaneira’s glassy natural harbor sheltered by the island’s jungled hills, and of nearby Pulau Gunung Api, dominated by its perfectly formed volcano. The sight lines were equally impressive. Contemptible though they were with local labor, the Dutch knew what they were doing when they built this place. Their enemies couldn’t sneak up on them, not even those pesky, well-armed English.

As the sun set, a bronze sky refracted on the black channel between Bandaneira and the nearby almond- and nutmeg-tree-wrapped isle of Banda Besar, where a handful of small villages cling to a rocky shore. The cries of chickens and children, the put-put of outboard motors, and the competing calls to prayer all mingled together in the gloaming. All that was missing was the cannon sounding to announce an approaching fleet.

But maybe the spice hunters were already ashore. “The big nutmeg harvest is in August,” said Paulman, the giddy 27-year-old Indonesian trader who was also on his first trip here. He’d recently been hired by DKSH, the Dutch conglomerate that owns L’Oreal and is expanding in Asia. His new gig was an old one: “I’ll come again next month and buy all the nutmeg I can and send it to the Netherlands.”

We visited Rumah Budaya, the archipelago’s main museum, with Abba on our second morning in town. Once owned by a Bandanese nobleman, this 200-year-old house with its original marble floors was piled with 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Portuguese coins, muskets, swords and a table cannon; massive meter-high clay pots in which European sailors kept drinking water on their old wooden ships; a nutmeg-plantation bell; and baskets used by the pickers.

“They were like slaves. They got paid very little and lived in one house together,” Abba said as we entered the parlor. He stopped cold in front of a vintage gramophone. As the rain started up again, he smiled, cranked up the old machine and needled the groove, and early-days swing warbled out of the turquoise tarnished-brass horn. He had to hum along with it. Couldn’t be helped.

Of course, the draw here has as much to do with its idyllic outlying islands as its colonial heart. Pulau Hatta—named for Indonesia’s founding father—is a stunning saucer of jungle-swathed limestone trimmed with luscious white sand. Offshore is some of the best snorkeling in the entire Indonesian archipelago, with vast schools of tropical fish, an underwater coral arch and stately table corals, where I spotted three turtles and a blacktip reef shark. Afterward, I lounged on a virgin beach, then wandered into Kampung Lama (“old village”), one of the island’s two settlements where concrete paths branched toward cinder-block homes brushed in sun-faded pastels.

It was harvest time and the whole town was suffused with the sweet smoked-cherry scent of cloves. Pak Sardin and his three brothers, two of their wives, and six children sorted a gargantuan pile of just-plucked clove flowers that looked like candelabras, and set them out on sheets to dry in the sun. I joined in and began separating flowers from stems as Sardin spoke of selling his bounty to one of 70 buyers in Bandaneira.

“Life is better for us now, since there is free trade,” he said, referring to the more-recent dark days of the spice trade, when Tommy Suharto, the dictator’s notorious son, was granted a clove monopoly that lasted throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s. First there were the Dutch and English… then Suharto, who sold all of his cloves to the cigarette manufacturers. But that was in the past, and while cash could be scarce and Pak Sardin still complained about weighty school fees, there was plenty of joy, togetherness and abundance here too. The clove season is long. Blossoms linger on trees for up to seven months, and when the waves and wind are too strong to fish, the men can always climb their trees and pluck them.

A similar rustic, laid-back vibe is palpable on the isle of Run, that once-astronomically valuable trading chip. There are stunning cream-colored beaches and chunks of limestone swathed in spice trees, with spectacular coral-crusted walls, ideal for diving, that sheer into the swirling cobalt depths.

Led originally by Nathaniel Courthope, the British claimed Run in 1616 and held on to its unparalleled nutmeg groves on and off for nearly 50 years. But thanks to the Dutch ability to execute blockades and at least one brutal massacre of the Bandanese, the British never managed to get their spices to market. At one point Dutch traders convinced Run villagers that the nutmeg bark was also valuable, so they began stripping—and killing—their own trees. This was just another dirty trick employed during the spice wars: the Dutch had sourced nutmeg on Banda Besar and wanted to prevent any competition. Before long, the entire Run grove was ruined. “All except for one tree,” said Abba, heading for the ruins of the old English fort on the island’s western edge. According to local lore, that plant weathered the war and sprouted new life. These days there are countless nutmeg trees growing on Run.

After a dive and a walk through town, we lunched on Pulau Nailaka, an obscenely sweet, petite, sandy crescent sprouting with scrub and ribboned with azure shallows. I laid back, listening and contemplating the egos and drama of centuries past and how none of that cacophony endured at the source of it all. I guess all that noise was exported to Manhattan.

Here there would always be blue sea, white sand and spice trees. Here there would always be space for silence. On the way back to Bandaneira, we encountered a pod of about 50 dolphins. I couldn’t help myself. I had to free-dive down, eavesdrop on their high-pitched chatter and spy their smiles as they wiggled through the infinite blue. Once they were gone, I surfaced, climbed back into the boat, watched the sun drop and listened to Abba hum all the way home.