The Doctor, The Dictator, And The Deadly Mosquito

It’s just after 2 p.m.

Filtered sunlight splashes through the teak forest, illuminating a network of stilted bamboo huts that stretches into the surrounding hills. Five neighborhoods are stitched together with pumpkin patches and banana groves, and enlivened by scavenging chickens, mud-soaked pigs, and packs of children dressed in rags. This place is not joyless, but it is desperate. The sour tang of rotting trash blows through camp.

Inside the hut that serves as the village health clinic, it’s always dark as night. The air is heavy; 13 patients sprawl on bamboo mats. Adam Richards, 33, an M.D. from the Bronx who was educated at Harvard and Johns Hopkins, sits next to 30-year-old He Ni Hta and her three young children.

Ni Hta’s eyes are vacant. She has been complaining of dizziness and numbness in her legs; her case has puzzled the young medics who staff the clinic. They’ve diagnosed Ni Hta with a thiamine deficiency known as beriberi, but Dr. Richards isn’t so sure. He takes her pulse, checks her blood pressure, and tests her reflexes. She appears on edge.

“What do you think caused this?” he asks.

Her eyes stay fixed on the woven bamboo floor. “The government destroyed our village a little more than a year ago,” she says. “We ran to a hiding place in the jungle and we stayed there. We couldn’t move for many days. My husband caught malaria. We had no medicine, and he got very sick. He didn’t eat for 2 weeks. Then he died.”

She was 4 months pregnant at the time. Still grieving, she managed to carry her children and their meager belongings for 3 weeks over steep jungle peaks to this camp, all the while dodging government soldiers.

“Four months after I arrived here,” she continues, “when I was 8 months pregnant, I had a stillbirth.” Birth complications, including premature delivery, have long been associated with malaria. Ni Hta may not have become ill like her husband—at least not yet—but she may well have been carrying the parasite, which, according to Dr. Richards, is what may have killed her unborn child.

Ni Hta’s 7-year-old son notices his mother’s despair and leans his head on her knee. She shoos him away coldly. Her three kids are charming. They smile and are engaged, but they’ve already lost a father. And now they may be losing their mother, too.

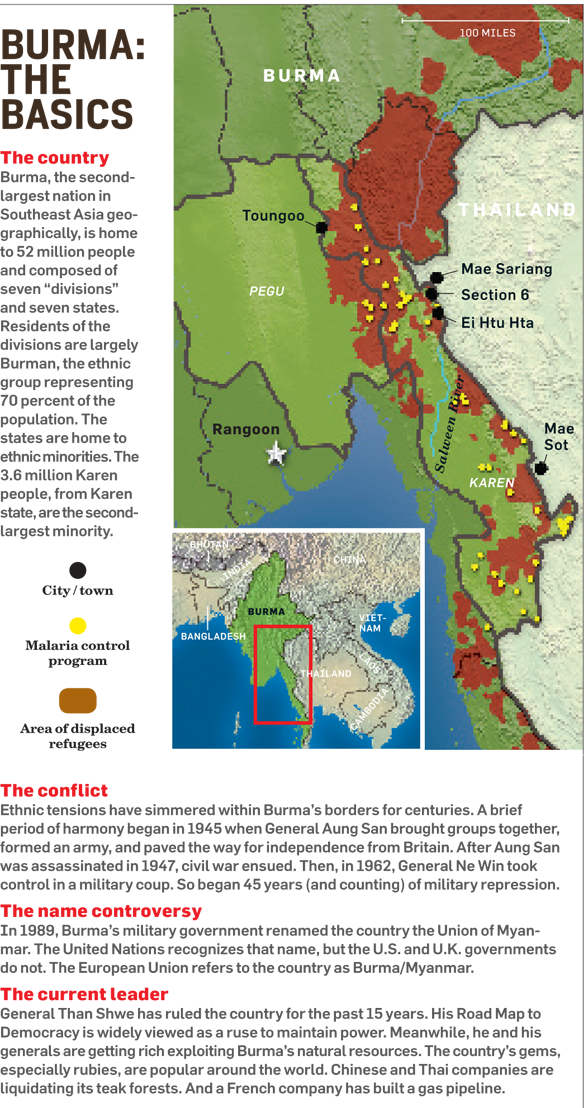

This is Ei Htu Hta (ee-TOO-ta), a makeshift village in eastern Burma’s Karen state. The nearly 4,000 people who live in this camp built for 600 have been run off their land by the notorious Burmese military government (calling itself, without irony, the State Peace and Development Council, or SPDC), which began its campaign in the spring of 2006 to create a buffer around its new capital.

The government has destroyed more than 3,000 villages in the past 12 years. Thousands have died. A half-million others have lost their homes.

Though the reason may be new, the practice is the same as it ever was. Tensions between ethnic minorities and the Burman majority date back centuries. Since the military regime seized power 45 years ago, it has been targeting opposition groups by clamping down on the civilians who support them. It is gradually taking control of Karen state—home to the second-largest ethnic minority in Burma—and selling the state’s natural resources such as timber to multinational corporations. In the process, the regime’s top leaders have become obscenely rich.

Ei Htu Hta is one of dozens of makeshift camps in eastern Burma. They house an estimated 500,000 displaced people who are in hiding, with very little cash to spend and even less freedom to work fields and move about. (The larger camps are located right on the Burma-Thailand border because the SPDC is less likely to attack them there.) Their leaders are exiled and living as legal or undocumented refugees in Thailand, and they are fed rations purchased by the Thailand Burma Border Consortium, a group of 11 international charities. These are communities in limbo. Danger and fear linger.

Forced relocation goes something like this: “They invaded at night. They came in shooting, and they killed many people,” says 28-year-old Hel Kler, who was born and raised in the Toungoo district, in northern Karen. “They set the thatched roofs on fire. They shot my uncle. They shot two of my friends. Two other friends stepped on land mines trying to escape. They blocked the roads to cut off our food supply. They torched the rice stores and the rice fields, and they burned the people working in the fields. After that they burned the village and set more land mines. And the people who tried to come back for their belongings stepped on the mines.”

The soldiers also typically either seize or slaughter the livestock. Some of the men are captured and forced to work as porters for SPDC troops. They march for weeks at a time carrying military supplies, and always walk in front so they will be the first to set off land mines. Young girls are often raped, village leaders are executed, and troops often demand the villagers’ cash. Other times, entire villages are emptied and interned at relocation camps. SPDC officials call them “model villages,” except these villages are overcrowded, fenced in, and watched by armed guards. If villagers disobey, they can be shot on sight.

“What’s happening here is crazy,” says Dr. Richards. “People should be outraged. This is a humanitarian crisis.”

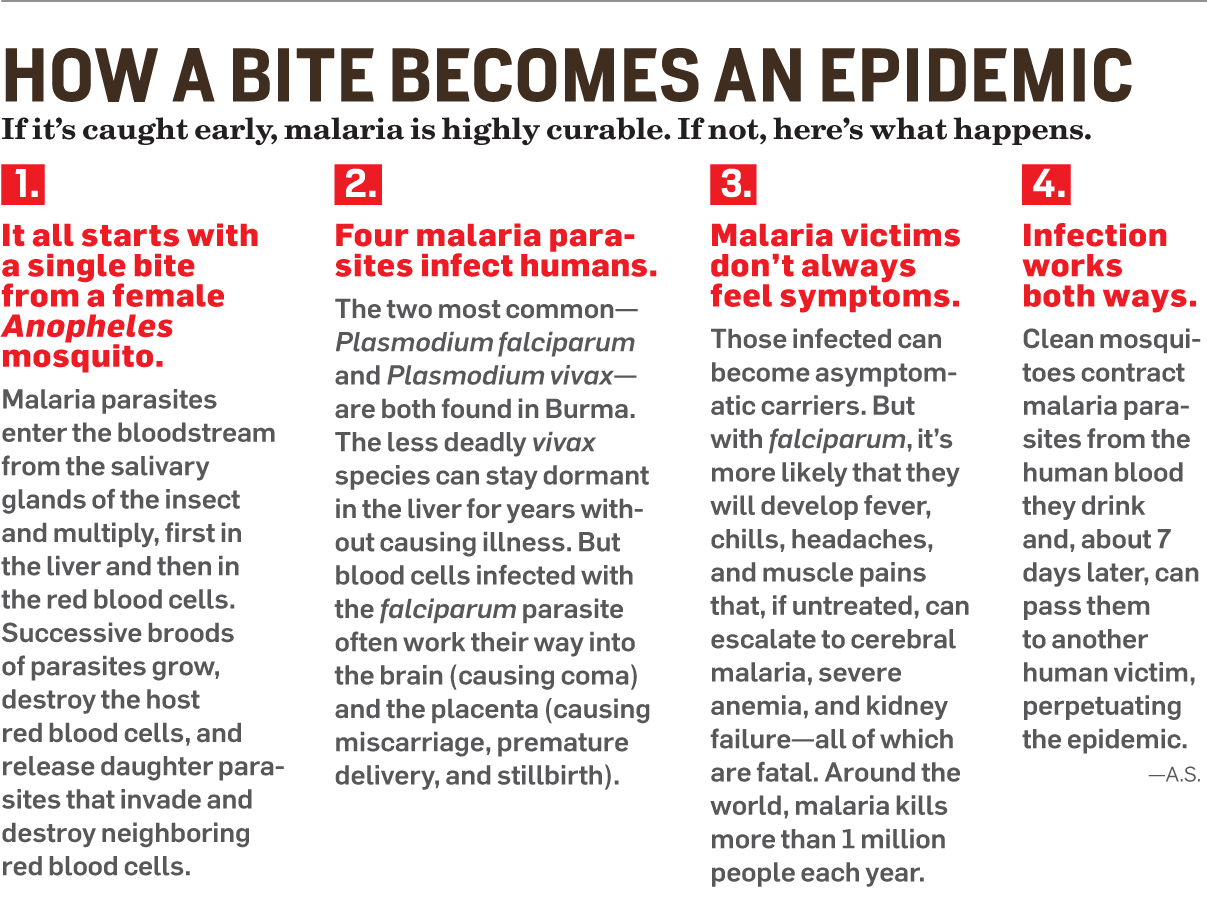

But bullets and land mines aren’t the only serious threats. Malaria is the number one killer in eastern Burma. “The SPDC has figured out that if people are cut off from shelter, nutrition, and medicine, nature will often finish the job,” says Dr. Richards.

In other words, malaria has been the SPDC’s secret killer for years.

“No one should die of malaria,” Dr. Richards tells me later that evening as we sit outside our hut in Ei Htu Hta watching children play in the muddy stream that snakes through camp. “It’s a disease of the poor, and it’s preventable.”

Those two statements have become his rallying cry. In 2003, Dr. Richards, then an ambitious med student and a new member of the Berkeley-based Global Health Access Program (GHAP), codeveloped a malaria control program with Eh Kalu Shwe Oo, the exiled chief of the Karen department of health and welfare. In just 2 years, thanks to simple, low-tech, and incredibly courageous field medicine, they reduced the number of malaria cases by 90 percent in the areas their medics reached. Still, malaria is responsible for 42 percent of all deaths in the region today.

I met up with Dr. Richards and Eh Kalu at GHAP’s satellite office in Mae Sot, Thailand, last September. We drove north to Mae Sariang and then entered Burma by way of longtail boat, traveling 2 hours along the Salween River to Ei Htu Hta. Mae Sot has become the base of operations for Karen’s exiled government, so it’s the best place from which to launch cross-border aid. Medics load up on medicine and supplies there, and then literally carry it into Burma on their backs.

Dr. Richards was making his eighth trip to Burma at an auspicious time. Buddhist monks hungry for democracy were assembling in the Burmese city of Rangoon to protest more than four decades of military rule. I suspected the protests would fail. This was my fourth trip into Burma, and I’d seen firsthand the handiwork of SPDC troops. Beating monks and shooting unarmed protesters on the street is practically quaint compared with the brutality that happens every day in Burma’s remote ethnic provinces, especially in Karen, home to an estimated 1.4 million people.

Dr. Richards and Eh Kalu are in the country to observe Karen medics such as 24-year-old Thu Ray, whose village was destroyed by SPDC forces in 2001. He wears jeans and a faded T-shirt. Drop him into a Starbucks, and Thu Ray would look like just another java-swilling hipster. He turns giddy when Dr. Richards enters the clinic here at Ei Htu Hta, immediately handing over medical charts and introducing him to patients.

In one corner, a 28-year-old man, teeth stained red from chewing too much betel, rocks his month-old baby girl in a hammock. His wife is out getting some air. The young couple has barely slept all week. When they arrived, the baby was near death. She had chronic diarrhea, and blood in her stool. Dr. Richards grabs a stethoscope and moves toward the hammock.

“She arrived with very bad dysentery and pneumonia,” says Thu Ray. “She coughed and cried so much.”

“You treated her with ampicillin?” asks Dr. Richards, as he listens to the child’s lungs.

“Yes. Injections for 3 days.”

“Good,” Dr. Richards replies. He checks her chart and turns to me. “The ampicillin is obviously important, but so are oral rehydration salts when breast milk isn’t enough. These men administered both and saved this baby’s life.”

He swings to the father and smiles. “Her lungs are clear. She’s doing well.” Thu Ray translates as the man nuzzles his child, relieved.

Next, Dr. Richards examines two 13-year-olds with malaria, a boy and a girl. Both are out of danger, but they will remain at the clinic with their families until their medication cycles are complete.

“Some patients come here from more than 100 miles inside Karen, so they must stay until they have completed their medicine and it’s safe to return,” says the soft-spoken Eh Kalu, 52, as a bright-eyed 13-month-old girl pops out from behind his leg to catch our attention. Her grandmother laughs and Eh Kalu chuckles as the toddler hams it up.

“She had a very high fever for several days,” says Thu Ray.

Dr. Richards glances at her chart. “Yes, malaria, but her fever has really come down. She’s doing great,” he says.

As we walk away, Dr. Richards puts Burma’s malaria problem into perspective for me: “If it weren’t for our program, those kids may not have survived, and the village of Ei Htu Hta would likely be in the midst of an epidemic.”

In Burma, malaria peaks during the rainy season, June through October. More people die of the disease in Africa, but here it’s more deadly per capita because residents aren’t exposed to the parasite year-round and don’t build natural immunity.

When Dr. Richards first arrived, malaria was the region’s biggest health threat, in part because it was becoming resistant to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, the anti-malarial drugs of choice, and had become resistant to quinine. There was little hope for change. “Nobody had ever tried to implement a malaria-control program in eastern Burma, at least not in a drug-resistant area of active conflict and where the people frequently migrate,” says Dr. Richards. “A lot of people were skeptical.

“Early diagnosis and treatment are key,” he continues. “In remote villages, the ability of our health workers to reach patients often means the difference between life and death.”

To bring health care to the displaced, the 500-plus medics—many of them Karen refugees—trek through dense jungle, dodge land mines, and evade hostile military units. Their salaries: $780 a year. Some work out of clinics like the one in Ei Htu Hta. Others work out of backpacks as they go from village to village, often sleeping in the jungle, for up to 6 months at a time. In addition to treating malaria, they’re trained to deal with pneumonia, dysentery, and malnutrition, perform amputations with camp saws on land-mine victims, and deliver babies. They’re general practitioners for families on the run. The SPDC does not want them here. In fact, the SPDC has torched half a dozen clinics and killed seven backpack medics since 1998.

At first, diagnosis was a significant challenge. “A number of illnesses, including dysentery and meningitis, have similar symptoms,” says Dr. Richards. It’s even more difficult when your only medical tool is a solar microscope. The solution: a 15-minute diagnostic test known as Paracheck, developed by a company in India. It’s like a pregnancy test, except you spread blood instead of urine on the stick. It’s 95 percent accurate.

As for treatment, Dr. Richards ditched the existing options in favor of a drug combination known as ACT. The malaria parasite can quickly mutate and become resistant to single drugs, often within a year or two. Using a combination improves the efficacy of the therapy. “We’re not seeing any resistance yet,” he says.

The program is now operating in 53 villages that are home to more than 40,000 people. Karen medics visit other villages, too, when possible. In total, they treat more than 270,000 patients each year.

How successful is the program? Malaria deaths are extremely rare in areas where the program is active. In fact, death occurs only if the medics can’t reach the patients because of SPDC patrols, or when Thai officials tighten the border a few times a year, typically after the SPDC makes a stink. “We started with just 10 medics,” says Dr. Richards. “It’s amazing to see what they’ve accomplished. This is their program now.”

Eh Kalu Shwe Oo is dignity personified. His isn’t a stuffy or haughty dignity. It’s in his quiet openness, warmth, incisive intellect, and tireless ability to listen. Just after sundown on our first day in Ei Htu Hta, Eh Kalu leads a succession of meetings.

First he sits down with the camp’s elected leaders. Mudslides have swallowed several classrooms, and the kids need a new school. Latrines dug too close to the creek are overflowing with untreated sewage after heavy rains. And there’s a water shortage—a major concern, considering that more displaced villagers are on the way.

“There are fresh springs in the mountains behind camp,” says Eh Kalu. “Let’s pipe water over to the new huts.”

Wang Htoo, the camp leader, looks downcast. “We have no pipe left,” he says.

Eh Kalu nods. “Don’t worry. I will make calls, find the money. We must have water. It’s good for health, right?” He chuckles, and the group laughs together in relief.

Next Eh Kalu meets with a handful of medics. They discuss challenging cases and go over the medicine and supplies. The medics look up to him, not simply because he’s the boss—he oversees the 200 field medics and advises the 76 five-person backpack teams—but because he’s one of them. Eh Kalu spent 18 years as a medic with the Karen National Liberation Army, where he too dodged SPDC bullets to treat both soldiers and villagers. He’s now based in Mae Sot, and his main duties are raising funds and coordinating with Karen leaders to maintain open supply lines and ensure the safety of his personnel. He’s always armed with two cellphones, so he can make calls and fire off text messages simultaneously. In short, he’s the linchpin that holds together the entire health-care system of a forgotten state.

The next morning, Eh Kalu and I take a walk through camp. We pass groups of uniformed children heading to school and timeworn men smoking their morning pipes. The wind carries sounds of crowing roosters, barking dogs, a rushing stream, and women smacking wet laundry on creekside boulders. Barefoot troubadours strum guitars and sing to giggling teenage girls whose cheeks are painted with thanaka swirls.

I spot an intensely beautiful woman dressed traditionally in a crisp, bright-pink sarong and carrying a baby strapped to her back. She is unusually tall for a Karen woman, and her long, lean legs and ample hips carve an idyllic profile as she strides along the muddy trail between bamboo huts. She turns and offers a smile, her dark eyes sparkling, before disappearing into a papaya grove.

“How does it make you feel,” I ask Eh Kalu, “that the SPDC wants that woman, that baby, and all of these people dead?”

He stops and offers a half smile. “I used to get very angry,” he says. “But that’s a young person’s reaction. I have to keep that anger inside and concentrate on how to improve the situation. Not think about revenge.”

He tells me that the Toungoo district in northern Karen is under attack, in “the worst offensive since 1997.” Battalions of soldiers are flooding the region, and thousands of newly displaced people are running for their lives toward Ei Htu Hta. To make room, Karen leaders have started a new section of camp, but unlike the current five, which are all on the same plot of land, Section 6 is hidden in the teak forest an hour north, up the Salween River.

Yes, the badly overmatched Karen National Liberation Army has been thoroughly defeated, but it does manage to warn villagers when SPDC troops are on the way. The alert system is so sophisticated that villagers can escape to designated hiding places in the jungle. That doesn’t mean the villagers are safe once they escape, however. “It’s very difficult and dangerous for our medics to reach people hiding in the jungle,” says Eh Kalu. “They could be killed or accidentally give away the location of the hiding place. We want to give health care to everyone in Karen. But it’s impossible.”

Two hours later, Dr. Richards, Eh Kalu, and I climb back into our boat and head toward Section 6 to meet the new arrivals. The mocha-colored Salween is about 650 feet wide, draped on both sides by impenetrable jungle that’s home to SPDC military positions. When SPDC scouts come into view, we veer hard to the far bank to avoid detection.

The camp is a quarter-mile walk from the river’s edge. We pass three young boys dragging bamboo to the site of what will be their new home. They are all from Toungoo. They tell me they spent 2 weeks hiding in the jungle, then trekked 15 days to reach this place.

There are seven medics in the village already. Not only are they testing for malaria and treating the sick, but they’re also collecting stories—human-rights data. “This information is important,” says Dr. Richards. “We’ve found that food insecurity, forced relocation, and forced labor are all associated with an increased risk of malaria.” And the risk is twice as high in households reporting more than one human-rights abuse.

“The fact that most medics are indigenous,” he continues, “helps villagers feel like they can speak freely.” Many also believe that by sharing their tragedy with the world, help will arrive one day.

As we stroll through Section 6, children follow us, women size us up, and men ignore us as they quickly dig latrines and build huts. About 300 displaced people are here, and 1,000 more are reportedly en route. Eh Kalu has already arranged for an additional team of medics to motor upriver, but there aren’t enough huts for 1,300 people yet.

Eh Kalu notices a woman standing in her doorway and stops. He’s still a medic, after all, and she doesn’t look right. “Are you okay?” he asks.

“I have malaria, but I’m feeling better,” says Blu Tu, 22, as her 3-month-old baby yawns in her arms and her 15-month-old son hides behind his dad.

Blu Tu’s case shows how displacement leads to disease. After her village was torched, she lived in the jungle for weeks. She was healthy at first and delivered her baby without complications. But at some point a tainted mosquito bit her. The symptoms began the day after she arrived at Section 6.

“It was raining and I was very tired. I went to take a bath, and afterward I felt a chill.”

“Did you go to the clinic?” Eh Kalu asks.

She laughs, embarrassed. “No. I waited 2 days. By then the fever was worse, so I went.”

The medics put her on ACT meds immediately. Her fever broke, and gradually she regained her energy. Luckily, she’s the only one in her family who became infected.

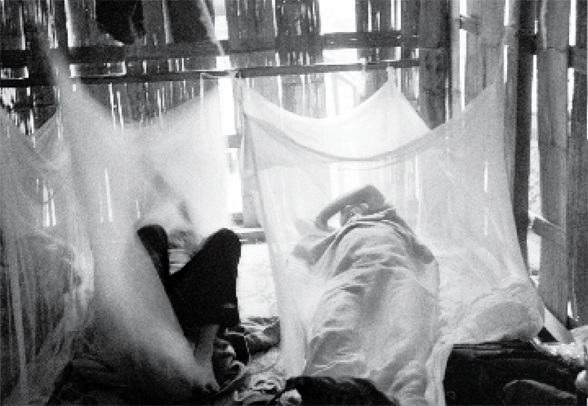

She leads us into her small hut, which is roughly 10 feet by 10 feet. We take off our shoes at the door and sit cross-legged in a circle on the woven bamboo floor.

“How many people live here?” Dr. Richards asks.

“Five.”

“But you have only two nets. Do you sleep under a net?”

She nods. Dr. Richards turns to Eh Kalu. “That’s probably why the malaria stopped with her.”

Distribution of insecticide-treated nets is also important for malaria control. Humans can infect mosquitoes as easily as mosquitoes infect humans. If someone in a household is infected and a clean mosquito bites him or her, the mosquito becomes a carrier. But if infected mosquitoes come in contact with the nets, they won’t live long enough to spread the disease.

If there aren’t enough nets for everyone, the next best option is to put the malaria patient beneath the mesh. “If the mosquito dies after biting an infected person, the cycle is broken,” Dr. Richards explains. “That’s how we gain the advantage.”

Before leaving Section 6 later that afternoon, we stop by the village church. Four weeks ago, this building didn’t even exist. Now it’s packed with people hoping for some kind of salvation. After the service, Shut A Paw, a young mother, notices us and smiles. But the little girl in her arms, her 6-year-old niece, becomes terrified and hysterical.

“The SPDC killed her father, my older brother,” says Paw as I follow her outside. “They came and took him and two other men and killed them in front of the whole village. My niece saw everything.

“I come to church to pray for peace,” she continues. “So one day we can go back home and be free.” She smiles and waves goodbye. Dr. Richards, Eh Kalu, and I hike back down to the river in silence.

The next evening, after a day of traveling, we arrive back in Mae Sot, Thailand. This isn’t a pretty town. The outskirts are rimmed with large camps built for the 120,000 Karen who were granted refugee status by Thai authorities over the past 10 years. Our driver veers down a rutted alley to the dilapidated compound, a huddle of two-story wooden buildings with concrete floors and cobwebs in the rafters, where Eh Kalu lives and works. Similar compounds are scattered throughout Mae Sot, filled with members of Karen state’s government-in-exile and pro-democracy Burmese activists.

“You know,” says Dr. Richards, after we drop off Eh Kalu, “it’s very dangerous for Eh Kalu and his staff here. Border groups have been infiltrated by SPDC spies, and Thai immigration officials can arrest and deport them at any time. But he’ll never quit, no matter the danger. He’s in a unique position, in which he can help people and promote democracy and political change at the same time.”

Of course, political change is often influenced through evidence and policy. That’s why Dr. Richards is a self-avowed public-health geek. And why the next day, he’s preaching the importance of inputs, outcomes, and needs assessments to a classroom of Karen medics.

“You need to count how many nets you see,” Dr. Richards tells them, “and ask how they’re being used. Then you have to write the answers down in your house-visit book,” he says, cradling an example. “This is our source of data. This is precious information.”

There are rumblings in the back of the room. A few medics are concerned that they won’t have time to collect all the data—they have too many patients to see.

“Of course your patients come first,” Dr. Richards responds. “But can you train a villager to do this? A volunteer?” Heads nod in agreement; a rumble of affirmation fills the room.

And because of this discussion, somewhere inside Burma a villager will soon go door-to-door in the malaria zone. What he or she learns will be translated by Dr. Richards and his team into food, medicine, and mosquito nets. Lives will be saved. Children will grow to adulthood. Karen communities will become stronger. And maybe, someday, a nation will find peace.

Related articles

Contributor To

Subscribe to my newsletter

Sign up for occasional updates on new stories, book releases, and behind-the-scenes writing insights - straight from Adam. No noise, just good writing.