The Jesus-Kissed, War-Fringed, Love-Swirled Rangers

On a sticky 90-degree day last November, the sun blazed high over a village in northern Karen, a province of 7.5 million people in southeastern Myanmar. At the edge of a riverside clearing, farmers dressed in rags, sweaty and soiled, trickled home from the fields to their thatched-bamboo huts for lunch. They chatted and laughed freely—until a mortar exploded 50 feet away.

Within seconds men in Myanmar Army uniforms strafed the village with semi-automatic gunfire. Shouting soldiers dragged women to the ground and held pistols to the men’s heads. The platoon leader wandered from hut to hut, using a torch to ignite grass roofs.

Then something strange happened. A young blond girl—dressed in black and wearing flip-flops, her face streaked with grease—suddenly leaped to the top of a boulder, holding a bow and arrow. Narrowing her eyes, she pulled back and fired.

“Way to go!” A lean, fit American guy, dressed in running shorts and an Army green T-shirt, emerged from the sidelines, clapping and cheering like a proud parent at a soccer game. “Did you see that? She jumped up like Robin Hood and just nailed the guy!”

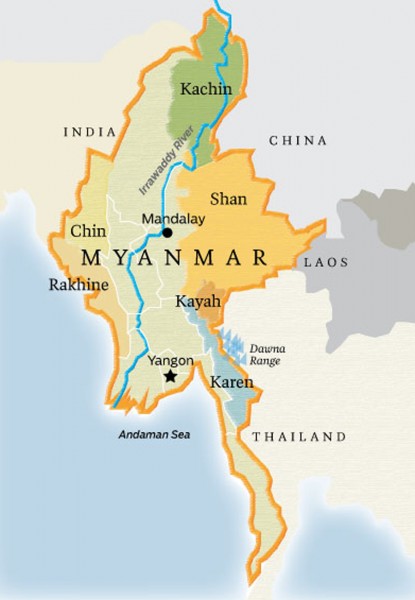

This was the 52-year-old founder of the Free Burma Rangers (FBR), a humanitarian relief outfit operating in Karen and other Myanmar states. I’ll call him Scott, which is not his real name. (Because the FBR’s work involves crossing into Myanmar illegally and could be shut down at any time—and because of the security risks I observed FBR teams take behind enemy lines—I agreed not to reveal the identity of the group’s founder or members of his family.) The blond girl is Scott’s 12-year-old daughter, and what I’d been witnessing was the kind of attack that has occurred many hundreds of times in the country’s ethnic regions—in the border states of Karen, Kayah, and Shan, among others, whose rebel militias have resisted Myanmar’s military since the country gained independence in 1948. Even as Myanmar’s government has made headlines for its recent reforms, the fighting has continued in some areas, and a full-fledged war has erupted in Kachin, where 90,000 people have been displaced since June 2011.

This time, however, the arrows were blunted and the bullets blanks. The mock village burning was the elaborate launch of the final two-day exercise at FBR’s six-week training session, at a place called White Monkey Camp. A former U.S Army Ranger and ordained minister, Scott founded the Free Burma Rangers in 1997. Run by a staff of Western evangelical volunteers and funded mainly by Christian churches, FBR trains teams of ethnic rebels to go toward the front lines, help evacuate internally displaced people (IDPs), treat the sick and wounded, perform reconnaissance of enemy troops, inform villagers and allies of their whereabouts, and document the Myanmar Army’s carnage with video, photography, and written reports, which they transmit to news organizations, NGOs, local governments, and church groups around the world.

The FBR’s work is dangerous. Rangers are often armed with whatever weapons they can find—shotguns, 22s, AK-47s—and have been the target of enemy fire on a number of occasions. Since 1997, 13 Rangers have died in the field—one caught and tortured to death by the Myanmar Army, others killed by land mines, malaria, and a lightning strike.

Scott runs five training camps each year, with the largest, held each November, at White Monkey Camp. This time there were 76 trainees in attendance, ranging in age from 18 to 36, representing seven of the country’s 135 ethnic groups. Most of them were rebels sent by the Karen National Union (KNU), one of the largest movements fighting for autonomy from the Myanmar government. Over the previous few weeks, the trainees had attended seminars in strategic reconnaissance and wilderness rescue and received specialized instruction from volunteer medics, engineers, photographers, and videographers. Beginning at 4:30 a.m. each day, they’d also undergone grueling physical conditioning, including climbing canyon walls and hours of sit-ups, push-ups, and trail runs. During the final mock-fighting exercise, they wouldn’t sleep or eat much.

As the smoke cleared, veteran Rangers split up to oversee one of 19 test stations for, among other things, orienteering, security, and rappelling. I headed over to the land-mine station, run by a shy, slender woman named Hsa Geh, who is 29. When she was 16, Myanmar soldiers murdered her parents and little brother in their Karen village during an invasion similar to the drill I’d seen today. One sister was raped and killed, the other shackled and imprisoned at a Myanmar Army base, never to be seen again. Geh escaped and lived on the run for two years before the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) took her in. She joined the FBR six years ago.

“Talk about tough, man,” Scott said as we watched Geh put her team through the paces. “A lot of our Rangers have stories like hers.”

Moments later, at the rappelling station, Scott—calves and biceps bulging, abs as ripped as a young Marine’s after basic training—was unhappy with the tie-off. After adjusting the line, he dropped over the edge of a river bluff, sans harness, and eased down, hand over hand, then smoothly climbed up before he allowed the first recruit to clip in.

I’d arrived at the camp a few days before. I’d spend the next week here, then trek with Scott and his recruits deeper inside Karen to the village of Tha Da Der, the first stop on a three-month FBR relief mission. It would be a rare look at the front lines of one of the more unusual relief efforts in the world—a humanitarian movement with both Bibles and guns.

I MET SCOTT IN Shan State in 2007, when I spent four days with him as he trained Shan State Army-South rebels for a relief mission there. My first impression: he is one Jesus-loving badass.

On that trip, he told me about his U.S. Army career, his relief work in Southeast Asia, the triathlon he’d won, and the mountains he’d climbed. At times he would begin to pray spontaneously. The only son of a Texas oil speculator turned preacher and a Broadway star (his parents met before his mother’s USO show during the Korean War), he was born in Texas but prior to his first birthday moved to Thailand, where his parents worked to build schools and cultivate Christians.

“Back then, Thailand was a lot like here,” Scott said, gesturing toward the surrounding mountains and jungles. “I learned to ride, swim, and shoot when I was five. I already knew that I wanted to be soldier.”

By the eighth grade he was an Eagle Scout. Ten years later, in the ’80s, he was leading an elite airborne strike force in Central America. A few years after that, following a stint as a U.S. Army Ranger, he joined Special Forces and relocated to Thailand. During his time in the Army, he began participating in triathlons—winning the Panama Studman—and climbing. He has summited Nepal’s 21,247-foot Mount Mera, Alaska’s Denali, the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc, and Mount Rainier (twice in one day). When he retired from the Army in the early ’90s, he earned a postgraduate ministerial degree from California’s prestigious Fuller Theological Seminary, then moved back to Thailand to work in Karen and Shan refugee camps on the Thai border.

In the mid-1990s, the Myanmar Army initiated a campaign to weaken rebel forces in the ethnic regions. It’s a conflict that goes back centuries, between the central Burmans—who account for almost 70 percent of Myanmar’s population and are largely Buddhist—and the 135 ethnic minorities in the states, who are also predominantly Buddhist but have their own languages, traditions, and rites.

Tensions escalated in 1947, after revolutionary hero Aung San, who’d crafted a constitution for a federal democratic Burma, was assassinated. Following years of upheaval, a military coup in 1962 put dictator Ne Win in power, backed by a junta of ruling army generals. Win turned Burma into a police state, censoring the media, imprisoning political rivals, and declaring war on rebel ethnic armies—a war that has continued, with varying degrees of violence, ever since, and which many believe is as much about the states’ resources and key border locations as it is about quashing ethnic rebellion. The repressive regime, which changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar in 1989, has been most violent in the states of Karen and Shan. Since 1996, according to the Thailand Burma Border Consortium, an alliance of NGOs that provides aid to refugees and displaced people, 3,724 villages have been torched, with more than a million people displaced and a large but unknown number dead.

Scott entered this tragedy in 1997, during one of the most ruthless outbreaks of violence, when the Myanmar junta—which was renamed the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) that year—launched a major offensive in Karen, Kayah, and Shan, slaughtering thousands. He heard the sounds of mortars and gunfire while working with Karen refugees near the Thai border, stuffed a pack with supplies, and headed toward the fighting in Myanmar, where he saw some of the 200,000 IDPs.

“I had four backpacks full of medicine, so I figured I would respond,” he said. On the way, he met a lone Karen rebel. Together they hiked to the front lines, where they treated refugees until the medicine ran out. The idea for the Free Burma Rangers was born.

As we talked in his solar-powered office at White Monkey Camp, Scott scrolled through a hard drive full of images documenting SPDC brutality—the contorted bodies of children buried in rubble, the bruised limbs and vacant eyes of rape victims, several landmine amputees. By the end of the army’s offensive, in 1998, Scott told me, there were four Rangers. In 2001, he held his first six-week FBR boot camp, modeled after his Special Forces training.

Today there are approximately 350 Rangers, divided into 70 teams operating in the states of Karen, Kachin, Kayah, and Shan. Each team consists of four to five Rangers: a team leader, a medic, a photographer, videographer, a security specialist to map their route and liaise with rebel armies, and a Good Life Club counselor, who is in charge of the education and health needs of village children. Once trained, the teams are deployed by veteran Rangers, who work with rebel militias and Scott to determine where to send them.

David Taw, a high-ranking member of the KNU, lauds the FBR’s efforts. “They make a very positive move because they help the ethnics help themselves,” he said. Scott “has a lot of credit with ethnic groups.”

“FBR has saved the lives of thousands,” said Roland Watson, the founder of the Burma watchdog site Dictatorwatch.org, “by treating life-threatening diseases, helping tens of thousands of people with less serious health issues, and, perhaps most important, bringing hope to a terribly oppressed population.”

But not everybody is thrilled about armed rebels trained by American evangelicals running through the mountains of Myanmar. “It is difficult to say that the FBR’s operations are humanitarian, which implies following principles of neutrality and impartiality,” says Richard Horsey, a former International Labor Organization representative to Myanmar who also advised the U.N. on the international response to the country’s 2008 Cyclone Nargis. “Rather, they are involved in a kind of solidarity work. There is no doubting their commitment and dedication. But the fact that FBR staff carry arms, cooperate closely with particular armed factions, and represents an evangelical Christian ideology in an area of significant religious tensions are all troublesome.”

It’s a criticism Scott has heard before. “Regardless of your religion,” he said, “the evil going on in Burma must be confronted. Little girls are being raped, villages burned. That’s wrong. I’m going to do something about it.” Scott has always been clear that the FBR trains soldiers in rebel movements to relieve the ongoing oppression from the Myanmar government. The FBR does not supply weapons to Rangers, but they are free to arm themselves. “A lot of times, Rangers have to put themselves in harm’s way, so we don’t have any qualms with them carrying a weapon,” Scott says, but strictly, he emphasizes, for self-defense. “Our role is not to fight the Myanmar Army, and we try not to.”

Meanwhile, late last year, with the world watching, everything seemed to change in Myanmar. After easing restrictions on a highly censored Internet, President Thein Sein, a former high-level general in the military junta, who came to power in 2011, released more than 600 political prisoners. Aung San Suu Kyi, San’s Nobel Prize-winning daughter, who’d spent 15 of the previous 21 years under house arrest, began meeting publicly with President Sein and was elected to parliament in April. Even the Kachin seemed to get a reprieve, as President Sein abruptly halted a controversial dam project on the region’s Irrawaddy River—which had ignited fighting between the Kachin Independence Organization and the Myanmar Army in June 2011—citing environmental concerns.

But despite encouraging political signs and the cautious optimism of some ethnic leaders, the fighting in Kachin continues over its lucrative jade mines and has been exacerbated by the extension of the Shwe oil-and-gas pipeline into China. In the state of Rakhine (formerly Arakan), long-standing tension between ethnic Arakan Buddhists and the Muslim Rohingya people erupted in a deadly race conflict in June, with reports of as many as 100,000 newly displaced people and government forces firing on unarmed civilians. “The conflicts in Burma won’t end until there are free and fair elections, a new constitution that guarantees ethnic self-determination, human rights, and a justice-and-reconciliation committee to address the crimes of the past 60 years,” Scott says.

For many in Myanmar’s states, where up to 450,000 IDPs are still hiding in the jungle, the FBR is their only relief.

MY FIRST MORNING AT White Monkey Camp, I woke before dawn to call-and-response chants of “Free Burma, Rangers! Free Burma, Rangers!”

The camp consists of two dozen bamboo structures, including Scott’s house, where he lives with his wife, Susan (not her real name), and their three children—two daughters, who are 12 and 10 years old, and a seven-year-old son—about two months a year. (The rest of the time they’re in nearby countries, on FBR missions in Myanmar, or in the U.S., where they spend about a month each summer.) A sign dangles from above the entrance to their home. A biblical reference, Philippians 4:13, reads: “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me.” There’s also a schoolhouse that doubles as a chapel, as well as an administration office, staffed by a revolving group of 10 Western evangelical volunteers.

Hulking mountains, dense jungle, and a creek surround the camp. The FBR’s Jungle School of Medicine is a short walk downstream. There, a volunteer American doctor, who ran a hospital in Pakistan, and his staff of volunteer physicians teach medics how to perform amputations, treat gunshot wounds, and cure malaria and diarrhea. Below that a whitewater river rages. The kids’ pet pygmy pig-tailed macaque, Wesley, is usually nearby.

Emerging from a bamboo lean-to, I watched as Scott and his recruits hammered out sets of push-ups, crunches, and pull-ups. When it came time for a training run in the hills, Scott set the pace. One by one, the recruits buckled as the trail went vertical, until there was only a single man on his heels.

Khaing Main Thenee, 24, a Buddhist monk from the port city of Sittwe, in Rakhine, marched against the junta in 2007 in what became known as the Saffron Revolution. When the inevitable crackdown came, Thenee and his fellow monks were beaten and teargassed. “We tried to express our desire for freedom peacefully,” he said, “and they beat us like dogs.” He shed his robes, joined the Arakan Liberation Party, and was sent here for training. Less than half his commander’s age, Thenee should have been able to fly by Scott, but he, too, faded during the final push.

Throughout the day, Rangers in training sat in tin-roofed classrooms listening to instruction from a volunteer—a retired Air Force colonel with 20 years of F-15 flight experience—or learned self-defense techniques in a nearby clearing from a former Marine who’d done 13 tours in Afghanistan and Iraq. Other Western volunteers included a former Amazon employee, a finance guru, a logistics expert, and two recent college grads, who handled administrative tasks and preparations for the FBR’s upcoming mission.

While I was at White Monkey, the Karen National Union was in active discussions with the Myanmar government about a cease-fire agreement. The government, Scott explained to me, wanted to foster peace through the development of infrastructure, like roads and dams, the idea being that tapping into Karen’s natural resources will provide prosperity and peace for all. But Scott and other Karen leaders, whom he’s formed close relationships with over the years, believe that if not for the Myanmar government’s military oppression, the Karen could approach multinational corporations or the World Bank to launch their own development projects, prospering without Myanmar’s help.

Later that night, he gathered his veteran Rangers and Western volunteers in the barnlike map room for an update on a meeting he’d attended on the Thai border the day before with exiled KNU leadership. “At the same time the army is attacking the Kachin, and in some places the Karen, they’ve asked for a cease-fire,” Scott told us. “So the KNU asked us to come and pray and think about what to do. I said the cease-fire is up to you, not up to the FBR. We will stand with your group regardless of your decision.

“But this war is not about development,” he continued, becoming more animated. “It’s about political freedom. God made us all free, but they won’t let you be free.” A gust of wind scattered loose fliers from the makeshift conference table to the floor. Scott smiled and said, “So let’s pray and be open to negotiation, but let’s stand by God’s principles.”

Earlier that day, I had learned that Scott planned to perform a double river baptism the next morning. While he does baptize those who ask for it, and though God is referenced frequently at camp, he makes it clear that he is not a conversion missionary and that all religions are welcome in the FBR. About 20 percent of Karen has been Christian since British missionaries arrived in the 18th century, but it remains mostly Buddhist. Still, the Buddhist Rangers I met weren’t bothered by FBR’s godly bent. “It doesn’t matter at all,” said Thenee, the former Buddhist monk. “Our main purpose is the same, that we work together to help the people.”

Others are less convinced. “It is a problem to try and persuade the people with humanitarian assistance to become a Christian,” said Mahn Mahn, chief of the Karen State Backpack Health Worker Team, which brings medical care to displaced people. “Personally, I believe in Christ, but religion and politics should be separate.”

Each evening, the Western volunteers, all devout Christians, convened for dinner with Scott and his family. Over meals of charred beef, limp noodles, and Day-Glo-colored cookies stored in ant-and-roach-killer tins, the conversation ranged from Noah’s Ark (myth or fact?) to homosexuality (is it a lifestyle choice?) to the true meaning of “Thou shalt not kill.” “The Hebrew translation reads: ‘Thou shalt not murder,’” Scott said.

When I wandered over to his office later that night, he took a more philosophical approach to the Scripture. “Whether you believe in God or not, we’ve all got freedom to do good or evil,” he said. “When people choose to do evil, either as individuals or as systems, and there becomes this pattern, especially when they say their intent is to destroy people, I think then you’ve got to stand.”

A satellite phone rang. On the other end was an FBR team member in Kachin. The team were hiding out among thousands of internally displaced people, documenting the destruction of 20 villages and other war crimes by Myanmar soldiers. Scott unfurled a map and busily copied down coordinates.

AFTER A WEEK AT White Monkey, it was time to begin the trek to Tha Da Der, where FBR Rangers would set up a medical clinic and perform reconnaissance on a Myanmar Army outpost three miles away. In July 2010, villagers in Tha Da Der had endured a brutal assault when nearly 200 invading Myanmar soldiers slaughtered livestock, pilfered rice stores, stole valuables, and torched the village.

We’d be joined in Tha Da Der by veteran diplomat Charles Petrie, a French-born former chief of the U.N. mission in Myanmar who was kicked out of the country in 2007 for publicly siding with the monks during the Saffron Revolution. Recently, he had been in discussions with Myanmar’s former minister of railways, U Aung Min, who President Sein had brought into his cabinet and put in charge of negotiating peace in the states.

As we set off, Scott told me about one of his most dangerous missions, in 2004, when he was leading more than 200 IDPs out of the jungle and his FBR team was fired on for 30 minutes. “An RPG landed 10 yards away, which should kill you, but it hit the slope and impacted out,” he said. Five months later, in northern Karen, his FBR team were cornered by the SPDC while taking a break near a stream. They sprinted off as the army lit up the trees. Two members of his squad returned fire, resulting in five enemy wounded and one dead. He and his Rangers escaped unharmed.

“Contact is rare, and we train our guys that if the army sees you, run, and the first couple of shots will probably miss,” he said, as Wesley, the family macaque, hitched a ride on his shoulder.

It didn’t take Scott long to put some distance between us on the trail. Thankfully, his wife, Susan, was soon at my side, as I stared nervously at a buckling bamboo bridge loosely lashed 20 feet above jagged boulders and Class IV rapids. “You can always crawl across,” she said.

Susan, who grew up a devout Christian in Walla Walla, Washington, had been studying to be a teacher when she met Scott in 1992. Their first date was ice climbing up Washington’s Mount Shuxton. “He gave permission to the adventurer in me,” she said. They were married in 1993 and spent their honeymoon trekking through Shan State. “I remember being in the back of a truck with rebel soldiers, getting jabbed in the ribs with guns and wondering, What are we doing here?”

Susan’s darkest hour arrived in 2005, when their son was just a month old, and their eldest daughter, five at the time, caught typhus. Her temperature soared to 104, and she was evacuated from White Monkey Camp. “As we were crossing the river,” Susan recalled, “she perked up and said, ‘When I get better, I’m going swimming!’” Two days later their daughter was fine, but their son had pneumonia. Still, she has embraced the lifestyle and finds FBR’s work fulfilling. She developed its Good Life Club program to help children affected by the conflict in Myanmar. “Out here, the highs are higher and the lows are lower,” she says. “It’s different than the Starbucks life, but that’s the gift of it.”

To ease the stress of constantly moving, Susan makes every camp a haven of domesticity. When we finally arrived at Tha Da Der, she went straight to the house they’d be staying in and began unpacking crayons and coloring books, setting out favorite snacks, and building a fire.

Our first morning in the village was a Sunday, and Scott and his family were due in church, a brand-new wooden building on a hill. “This time last year, it was all scorched earth,” he said. “The army had burned their church and all the houses to the ground.”

Later, I met with Saw Nay Moo Thaw, 45, the former local director of the Karen department of education and a longtime freedom fighter and FBR ally. He showed me the new bamboo school, where nearly 200 children huddled in open-air classrooms. High on a far wall, there was a small battery linked to a rooftop solar panel—Tha Da Der’s only current of electricity. “FBR give us this after the burning,” he said, “so the children can study at night.”

In the rice fields, Ranger medics had set up a tented clinic, and about 80 people had arrived from the surrounding villages for care. I could hear the sounds of an American gospel song being sung nearby by 150 Karen kids, a handful of Rangers, and Susan:

Do I love my Jesus

Deep down in my heart

Do I know my Jesus

Deep down in my heart

Yes, I love my Jesus

Deep down in my heart

THE NEXT MORNING, AT 5 a.m., 19 men gathered for a reconnaissance mission to the Myanmar Army outpost, among them Thenee, a handful of KNLA rebel soldiers, and their general Baw Kyaw. For two hours, we hiked through mine fields to within a quarter-mile of the army camp.

Scott and I leaned against a tree pocked with bullet holes and took turns peering through a Swarovski scope onto a cut in the jungle where a single Myanmar soldier stood next to a fire, making rice. His post, powered by a flexible solar panel, was fronted by the region’s only road. Although we were well within rifle and mortar range, the scene was oddly serene, even as seven more soldiers emerged from their tents. “They probably have only 20 or 30 guys down there,” Scott said. “But in 2007, we saw 400 soldiers, 70 trucks, and nearly 60 prisoners chained together.”

Thenee snapped photos with a Lumix camera. “In two weeks, it will look very different,” Scott whispered. According to Rangers in the field, there were two bulldozers just days away. “They want to widen the road, which could mean more soldiers and more attacks.”

It’s not unreasonable to look at Scott and wonder what exactly drives him to risk his family’s well-being for a battle that, by all rights, is not his to fight. Some believe that, because of his relationships with rebel leaders and his desire for freedom in the ethnic provinces, he may actually be perpetuating the conflict.

“For a long time, groups like KNU and KNLA had no other real support,” Petrie told me. “But the challenge is how do you transform a solidarity movement that is assisting in resistance to become more proactive in the peace process?”

As for Scott’s motivation, he admitted that he’s partly driven by the physical adventure of his work and by seeing justice in Myanmar. But he says it’s more than that. “What we’re doing out here is bigger than democracy or freedom,” he said. “It’s about love. If I’m bleeding out on a trail, wondering why I did this to my family, I’ll have peace knowing that I carried out God’s love to help people.”

In the 10 months since I left Myanmar, the rebels have embraced more peace—government cease-fire agreements have been signed with Shan, Karen, and Kayah rebels. After initial resistance to the proposed cease-fire, even Scott entertained the possibility of a new era. In March, he had a chance meeting with Aung Min, the leader of Myanmar’s cease-fire delegation, who opened the door for the FBR to communicate with Myanmar government officials, which Scott is following up on. The two also prayed together. “I felt God’s love with us,” Scott wrote in an FBR report.

Yet the prospect of peace remains cloudy. There are gun battles almost daily between the Kachin Independence Organization and the Myanmar Army, and there’s been a buildup of troops in Karen, as well as incidents of forced labor. Despite the cease-fire in Shan, FBR teams report renewed fighting there recently.

“I worry that what’s happening is a change of mind, not a change of heart,” Scott said when I reached him by phone in September, as he was making plans for this year’s White Monkey training camp. “You tell me you want peace and then bring more people in my front yard instead of getting out? That doesn’t show sincerity.” U.S. lawmakers, who in August renewed sanctions against Myanmar for another year, appear to agree.

When I was in Myanmar, during our hike back to Tha Da Der after the recon mission, I asked Scott if he thought Karen State would ever see peace. “I truly believe that if you join your will with his, God can use you to achieve the things he cares about, which are truth, justice, freedom, and love,” he said. “When this war is over and Burma is free, the ethnic resistance won’t be able to say it was weapons that got us there, it will be through God. And I’ll be able to say, ‘Thank you, God, for that ride.’”